This month marks the ten-year anniversary of the 7.0 magnitude earthquake that devastated Haiti. The epicenter was near the nation’s capital, Port-au-Prince, home to 3 million. The January 12 quake wreaked havoc, becoming one of the largest natural disasters in human history. The Haitian government estimated that as many as 300,000 died, hundreds of thousands were injured, and more than one million were rendered homeless as more than 250,000 buildings collapsed. The region’s infrastructure—power, transportation, communication, healthcare and education systems—suffered severe damage and destruction.

Scores of nations and millions of people worldwide responded with aid and support. In the first few days and nights before U.S. troops arrived to clear the way for and deliver desperately needed humanitarian assistance, Haitians had to survive. Most were afraid of returning to their damaged homes and fragile buildings because of possible aftershocks. Instead they took refuge on the streets and in public parks and squares surrounded by unimaginable piles of rubble and coated by the ubiquitous fog of pulverized concrete that hung in the air. Getting through the shock of the quake, and seeing their loved ones die and possessions destroyed, they needed to draw deeply on their inner and collective strength. In the face of despair, they found strength in song. Hundreds of thousands sang through the night—anthems and hymns and songs of resilience and hope. The songs, deeply rooted in Haitian culture and history, were expressions of their very identity as a people and community, rallying their spirits, and buttressing their courage despite the lack of food, medical care and shelter.

It was an unbelievable evocation of humanity in the face of unimaginable catastrophe. One could not but admire the Haitian peoples’ will, tenacity and reservoir of collective experience. Thinking of material needs, we often forget how important culture, religion, identity and basic beliefs forged through a people’s history are in their surviving a disaster. People don’t forget their culture in such a time of need, instead they take refuge in it—praying harder, singing louder, holding on tighter to each other.

The importance of culture in surviving the earthquake and eventually recovering from it was made clear to me and others at the Smithsonian Institution as our fellow Haitian colleagues responded in the first few days. Patrick Vilaire, a sculptor and grassroots cultural heritage worker, rescued books and artifacts in the rubble. Parents and teachers rushed to the devastated Holy Trinity Episcopal Cathedral to recover musical instruments precious to their children from the teetering music school building. Artists from the Centre d’Art pulled paintings out of their pancaked building in order to save decades of Haitian artistic creativity.

Patrick Delatour, the minister of tourism and historical architect, was appointed by Haitian president Rene Preval to lead the recovery planning effort. Patrick had been a fellow at the Smithsonian in the 1980s, and in 2004 was part of a team of Haitian cultural leaders who organized and curated a program at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival marking the 200th anniversary of Haitian independence—when the Haitians defeated Napoleon’s army, became an independent nation and abolished slavery. Among that team was Geri Benoit, former first lady of Haiti; Olsen Jean-Julien, more recently Haiti’s minister of culture; Vilaire; and others who played supportive roles, including Georges Nader, leader of Haiti’s largest museum and art gallery; Michelle Pierre-Louis, head of Fokal, Haiti’s largest cultural and educational foundation and more recently Haiti’s prime minister.

Delatour told me we needed something like the “Monuments Men,” the famed division of the U.S. Army that rescued the cultural treasures of Europe from Nazi destruction in World War II. The Smithsonian wanted to help our Haitian colleagues, but neither we nor any other organization had the template or funds to do so.

We were, though, inspired by the cultural rescue work of the U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield , led by its founder, Cori Wegener—who had served as a U.S. Army civil affairs officer and “Monuments Woman” after the 2003 invasion of Iraq and helped restore the Baghdad museum, and the American Institute of Conservation , led by Eryl Wentworth, which in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, had trained about 100 conservators in disaster response. Their expertise helped guide our plans for Haiti. In collaboration with the Haitian government, institutions, and cultural leaders, we mobilized. Along with the U.S. President’s Committee for the Arts and Humanities, the Department of State and USAID, the Department of Defense, the Institute for Museum and Library Services, the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities and others, we initiated the Haitian Cultural Recovery Project. Thanks to producer Margo Lion, crucial funding came from The Broadway League, New York theater owners who understood from their experience of our great disaster—9/11—how important culture was to the spiritual and material recovery of a nation.

Immediately we launched a drive to send paints, canvasses and brushes to Haiti’s Nader Gallery to be distributed to Haitian artists, so they could “paint the earthquake” and the aftermath. Our Haitian Cultural Recovery Project established a base of operations in a former UN building and compound in Port-au-Prince. Kaywin Feldmen, then head of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, agreed to detail Wegener to the Smithsonian to help guide the project. We hired a staff of about three dozen Haitians led by Jean-Julian and Smithsonian retired conservator Stephanie Hornbeck. We acquired generators, vehicles and equipment, established conservation labs, and hosted more than 120 conservators and cultural experts from the Smithsonian, and thanks to the American Institute for Conservation, from numerous American institutions such as Yale, the Seattle Art Museum, the Maryland State Archives, and others, as well as international organizations including the International Center for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) and UNESCO. We organized an exhibition of Haitian children’s earthquake art at the Smithsonian, mounted exhibits of Haitian art at several galleries, and hosted Haitian musicians and craftspeople at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival.

After two years of work, we’d trained more than 100 Haitians from more than 30 museums, galleries, libraries and archives in basic conservation, saved more than 35,000 paintings, sculptures, artifacts, rare books, murals, archives and other Haitian treasures. We built and improved collection storage facilities at MUPANAH—the national history museum of Haiti, the national library and archives, Holy Trinity Cathedral, the Centre d’Art , ISPAN—the national cultural heritage preservation organization, and other cultural venues. We’d also restored some key works for the Presidential Palace, the Nader Gallery, the Centre d’Art and other institutions. With Yale University’s conservation center, we’d run an advanced internship program, and with help from the Stiller Foundation and USAID, we’d established and built a Cultural Conservation Center at Haiti’s Quisqueya University to preserve artworks and to train the next generation of conservators.

So, where do we now stand a decade after the earthquake?

Haiti’s overall recovery has been long and hard. Much of the billions of dollars in promised internationally aid never arrived. There was no large-scale construction of new homes, nor repair of damaged homes and institutions, no new roads, and only some replacement of infrastructure. It took years to just clean up the 10 million cubic meters of rubble—the equivalent of filling up almost 100 sports stadiums. Though there was a peaceful transition of presidential power from Rene Preval to Michel Martelly, there were difficulties with the legislature and local civic authorities. Following the controversial election of a new president, the country has experienced considerable protest and unrest. Economic stability and daily life for millions remains a challenge.

On the cultural front, artists and advocates have endured and made substantial progress. The Quisqueya University Cultural Conservation Center employed Smithsonian- and Yale-trained conservators Franck Louissaint and Jean Menard Derenoncourt to restore paintings and provide preventative conservation training to those in public and private galleries. The Center, led by Jean-Julien, has also organized cultural activities to increase public awareness of cultural conservation and has aided other organizations in fundraising.

The Nader Gallery recovered more than 14,000 of its paintings and Smithsonian-trained Hugues Berthin has treated some 2,000 of them. Tourism has suffered given instability, thus art sales for this and other commercial galleries in Haiti have slumped. But creativity continues both in-country and beyond. The gallery has promoted both iconic Haitian masters as well as new artists and has mounted exhibitions in Haiti, Paris and Athens. It is currently planning for the 2020 Sydney Biennale and a Biennale in Haiti for 2021. Perhaps most significantly, the gallery established the Fondation Marie et Georges S. Nader with a collection of 863 paintings and art objects selected carefully by family members and art historian Gerald Alexis. The selection includes museum quality pieces created by both well-known and lesser known Haitian artists over the last century and represents the evolution of Haitian art. The goal is to exhibit the collection and also make it the foundation of a new public art museum.

MUPANAH, the national history museum, has engaged two of the conservators who trained with the Haiti Cultural Recovery Project to help manage and conserve its collections. The National Archives improved its 19th-century collection and is seeking support for new facilities. Holy Trinity Episcopal Cathedral is housing the remnants of three surviving larger-than-life murals that decorated its walls, and plan reconstruction for the future. Its boys’ choir has continued to perform over the years, including for tours of the U.S. and annual performances at the Smithsonian.

Le Centre d’Art has made enormous progress. Founded in 1944, Centre d’Art was the historical leader in recognition of Haiti’s artists and the promulgation of their art internationally, starting with seminal acquisitions by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in the 1950s. The collections of Centre d’Art consisting of more than 5,000 Haitian paintings, drawings, iron sculptures and other works and thousands of archival documents were severely compromised by the 2010 earthquake and initially treated by the Haiti Cultural Recovery Project. Ever since, the collection has been conserved, rehoused and studied, thanks to support from L’Ecole du Louvre, the William Talbott Foundation, Open Society Foundations and FOKAL . Most recently, the Centre d’Art joined the Louvre, the National Gallery of Art, Tate Modern and others in receiving prestigious recognition and substantial support from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project —enabling it to do more sophisticated restoration and conservation work in collaboration with the Smithsonian. It was an honor for me to attend the awards ceremony hosted at MOMA by Glenn Lowery and Bank of America’s Rena Desisto, and to stand with Centre board chair Axelle Liautaud and members Michelle Pierre-Louis and Lorraine Mangones in front of a Hector Hyppolite painting exhibited in the museum’s gallery.

Despite the destruction of its main building, the Centre has over the years produced exhibitions, held instructional programs and classes, and served as a meeting place for and supporter of Haitian artists. Centre d’Art recently purchased a historical, 1920s gingerbread-style mansion—Maison Larsen, to serve as a venue for its collections, exhibitions and programs. Support for the $800,000 purchase comes from the Fondation Daniel et Nina Carasso and Fondation de France.

A good deal of restorative work is needed to make this marvelous building operational, and funds for that are being raised.

Finally, the Haiti cultural humanitarian effort had great consequences beyond its shores. When Superstorm Sandy hit in 2012, the Smithsonian responded with many of the same partners that had mobilized for Haiti, and aided galleries, collections and museums in New York. This led to the Smithsonian partnering with FEMA to lead the Heritage Emergency National Task Force, which has since responded to saving cultural items from flooding in Texas, South Carolina and Nebraska, and from hurricanes in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Smithsonian formally established the Cultural Rescue Initiative with Wegener as director, coordinating the work of numerous conservators, collections managers, and experts from divisions across the Institution, and gaining federal appropriations and support from the Mellon Foundation, Bank of America, the State Department and many others. The Haiti effort provided a model of how U.S. government agencies and cultural organizations could collaborate to save heritage in disaster and conflict situations. That is now enshrined in the Preserve and Protect International Cultural Property Act , and the U.S. government, multi-agency Cultural Heritage Coordinating Committee. The Smithsonian, particularly its Museum Conservation Institute (MCI), works closely with the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security on training investigators to prevent the looting and trafficking of cultural treasures.

MCI has taken the lead in training hundreds of Iraqis in cultural conservation at the Iraqi Institute for the Conservation of Antiquities and Heritage in Erbil to reverse destruction by ISIS and others. Currently, the Smithsonian is working with Iraqi partners to stabilize the ancient Assyrian archaeological site of Nimrud and with the Louvre and Aliph Foundation support to safeguard and restore the Mosul Museum—both of which were severely damaged and looted by ISIS.

The Smithsonian has also worked in areas of Syria, Mali and Egypt to safeguard cultural heritage in light of conflict and terrorism, and in Nepal following a cultural devastating earthquake in the Katmandu Valley. Working with the University of Pennsylvania Cultural Heritage Center and others, the Smithsonian has engaged in research projects to better understand and respond to cultural destruction, and with ICCROM and the Prince Claus Fund, helps train professional cultural first responders from around the world.

Working with the Department of Defense and Defense Intelligence Agency, the Smithsonian, along with partners, helps encourage knowledge of U.S. law and international treaty obligations with regard to the protection of cultural heritage. And recently, as Haitian leader Patrick Delatour perhaps envisioned, the Smithsonian signed an agreement with the U.S. Army to train a new generation of Monuments Men and Women capable of addressing the complex issues of cultural preservation in today’s world. In short then, the Haitian experience provided the means for the Smithsonian, joining with many, many partners, to do a better job of safeguarding the world’s threatened human heritage.

The Crazy Superstitions and Real-Life Science of the Northern Lights

In 1859, a record-breaking aurora borealis shimmered across nearly the entire northern hemisphere and was visible as far south as Cuba. One of the witnesses to this historic heavenly display was the artist Frederic Edwin Church, who saw the event from New York City.

One of the 19th century’s most celebrated landscape painters, Church was also a “science nerd,” according to Eleanor Jones Harvey , the senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum . In Church’s estimation, the study of science and the creation of art went hand-in-hand. “One of the things that makes Church so charming is that he did believe as an artist that you should also aspire to be a scientist and really know your material,” says Harvey.

A new episode of the museum’s web series “Re:Frame” takes a look at the dramatic convergence of solar science, arctic exploration, the Civil War and American art in Church’s 1865 painting Aurora Borealis .

Church counted among his friends many scientists and technological innovators, such as Cyrus Field , the creator of the transatlantic cable, and explorer Isaac Israel Hayes , whose 1861 arctic expedition is memorialized in Aurora Borealis . In fact, Hayes shared his sketches from the expedition with Church, who used them to draft his scene of Hayes’s ship stranded in the frozen arctic waters.

In the painting, a faint but visible light emanates from a window in the schooner. A dogsled team can be seen approaching the ship, though the fate of its crew is far from certain. While this dramatic rescue scene plays out in the foreground, a magnificent blue, orange and red aurora blankets the otherwise dark and immense sky in the top half of the painting.

The massive aurora that Church witnessed in 1859 was not his first encounter with the northern lights, nor would it be his last. In fact, conspicuous auroras, comets and meteors were not uncommon during this time period; and because of the charged political climate of the Civil War era, for Church and his contemporaries, the appearance of an atmospheric phenomena in the sky presaged something of significance.

During this unsettling time, anxiety and uncertainty hung like ether over a public that viewed these “nocturnal, unhinged rainbows,” as Harvey calls auroras in her book The Civil War and American Art , as divine omens.

“Auroras are weird, however, because they’re kind of a malleable portent,” she adds. “They can mean what you want them to mean.” For example, in the North, when the Union appeared to be winning the war, an aurora in the night sky was viewed as a talisman of God’s favor. By contrast, when the war seemed to be going in a less favorable direction, another aurora was deemed a portent of doom, a sign that the world was ending. In the absence of the scientific understanding of the phenomenon, these superstitious interpretations were given even more space in the collective understanding of the day.

Auroras are “a manifestation of what we now call space weather,” says David DeVorkin , the senior curator of the history of astronomy and the space sciences at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum . Just as meteorologists study conditions in our atmosphere in order to forecast the weather, space weather scientists study conditions in our solar system, some of which are known to produce effects visible on earth.

“The Earth’s atmosphere is reacting to very high energy particles coming from the sun, when the sun burps, you might say,” says DeVorkin. These particles are then caught by the Earth’s magnetic field, which “focuses them in the northern and very far southern latitudes.” The dynamic motion , characteristic of an aurora, is due to the fact that “the particles themselves are moving along,” he says.

“An aurora will wave, it will jump, it will flicker,” says DeVorkin, “They happen to be pretty.”

While the magnificence of auroras in Church’s time—well documented not only in newspapers, magazines and scientific journals but also in poems and, of course, art—resonates with us in the 21st century, the unsettling feeling that accompanied the presence of auroras during the Civil War era situates Aurora Borealis in an unparalleled historical moment.

When Frederic Church began work on this painting in 1864, says Harvey, “it’s not 100 percent clear that the Union is going to win. We don’t really know how this is going to turn out.”

In this way, the aurora that Church includes in his painting represents a dramatic tension like the one playing out in the drama of Hayes’s stranded ship—which was, fittingly, named the SS United States . What’s ultimately going to happen? Will the Union endure? And if so, what will the reunited United States look like? It’s all TBD.

Ultimately, Church’s Aurora Borealis is, Harvey points out, “a cliffhanger.”

Frederic Edwin Church's 1865 Aurora Borealis is on view on the second floor, east wing of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

How the U.S. Government Deployed Grandma Moses Overseas in the Cold War Canceled Culture

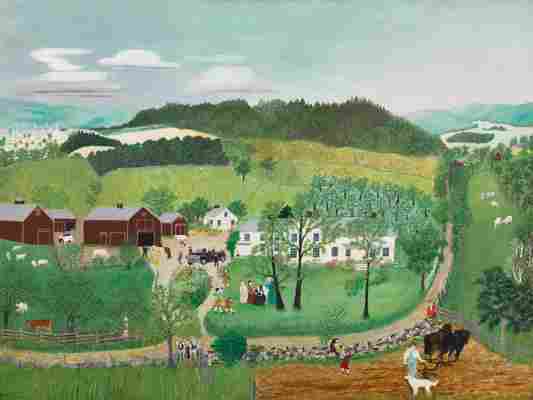

For someone who didn’t get serious about painting until her 70s, Anna Mary Robertson Moses managed a singular artistic career. She made her debut in New York City’s highly competitive art scene at the age of 80 with a 1940 gallery exhibition, “What a Farmwife Painted.” Later that year she grabbed headlines when she participated in the Thanksgiving Festival at Gimbels department store in Manhattan. She looked back on that moment in Grandma Moses Goes to the Big City , a 1946 painting of the lush countryside near her home in Eagle Bridge, New York. The Smithsonian American Art Museum recently acquired the painting.

By the end of the decade, a cottage industry of greeting cards, upholstery and decorative china bearing reproductions of her idyllic country scenes had made Moses a national celebrity. In 1955, she appeared alongside Louis Armstrong in the first color episode of Edward R. Murrow’s “See It Now,” and in 1960, one year before her death, Life magazine celebrated her 100th birthday by putting her on the cover.

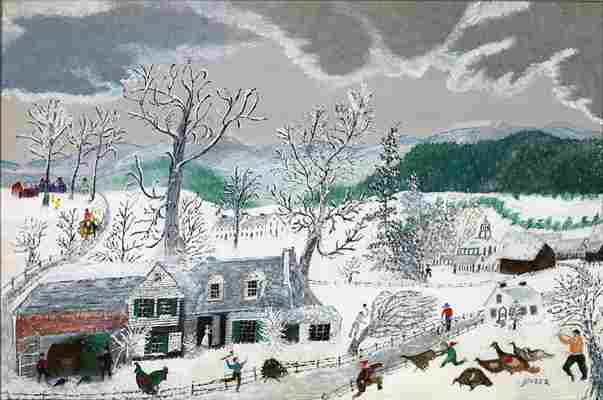

Yet in one of the most unexpected dimensions of her career, Moses also became an unlikely government asset in the Cold War, as I found while investigating how Moses benefited from U.S. government efforts to project a rosy vision of America throughout Europe. Between June and December of 1950, a government-backed exhibition of Moses’ picturesque American scenes toured six European cities. At the U.S. Embassy in Paris in December 1950, works like Here Comes Aunt Judith , depicting a family gathering at Christmas, were lauded by many. “It is a great pleasure to walk through such an exhibition, where the soul is devoted to the peaceful life in the quiet streets or in the warm interiors, in the midst of animals running loose or women working quietly,” one French critic wrote.

The idea that art could provide, as the late art historian Lloyd Goodrich put it, a “fallout shelter for the human spirit,” was a major motive behind the aggressive promotion of American art, music and literature across war-ravaged Europe. Propagandizing the fruits of liberal democracy in the face of Soviet communism was another objective. One Foreign Service officer who was involved with the Moses show declared that the exhibition had been as valuable as “pure gold” in promoting “the core of our national character which we are endeavoring to articulate in opposition to the efforts of the communists.” Moses’ paintings in particular fulfilled a key objective of Cold War cultural diplomacy: combating Soviet portrayals of Americans as mere capitalist dollar-chasers. The poet Archibald MacLeish, a Librarian of Congress under Franklin D. Roosevelt, wasn’t bothered by the absence of conflict, poverty or suffering in her work, arguing that art sent abroad should “subordinate to some extent the worst elements of our culture.”

As a Mayflower -descended matriarch old enough to remember hearing the news of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Moses had unassailable patriotic credentials. President Harry Truman was a prominent admirer: When the two met at an awards ceremony in 1949, he reportedly told the audience that he and Moses “were in complete agreement over ‘ham-and-egg art,’” his derisive term for abstract painting, then becoming increasingly favored. Truman would go on to welcome paintings by Moses into the official White House collection and, later, his own home.

Her fame was so wide-ranging that—ironically—it eventually caused her to be written out of the history of midcentury American art. This erasure began with the American art critics of her day, who were frustrated, especially in the wake of her European tour, by her ascendancy. Clement Greenberg, an enemy of kitsch and its seduction of mass taste, preferred to celebrate figures such as Jackson Pollock, whose elimination of pictorial content in his drip paintings challenged the appetite for realism that fueled Moses’ popularity.

Today, as the art world rethinks its traditional emphasis on white male artists, Moses is being re-evaluated. She will figure prominently in an exhibition I am curating next year at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, and her work will be showcased on an even larger scale in a solo exhibition being planned by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

It’s a pretty safe bet that audiences will once again find solace in Moses’ verdant hills and snow-covered farmscapes. And perhaps now that she is no longer perceived as a threat to the acceptance of abstract art, which now sits comfortably within the canon, the critics will finally come around too.

In 1947, Congress called off an International tour of American art for its alleged subversion