Understanding the regional impacts of a global problem like climate change can be challenging. Melting glaciers in Greenland or Antarctica cause sea level rise near coastal communities thousands of miles away. In places like New Orleans, for example, about 46 percent of sea level rise is due to ice melting around the globe.

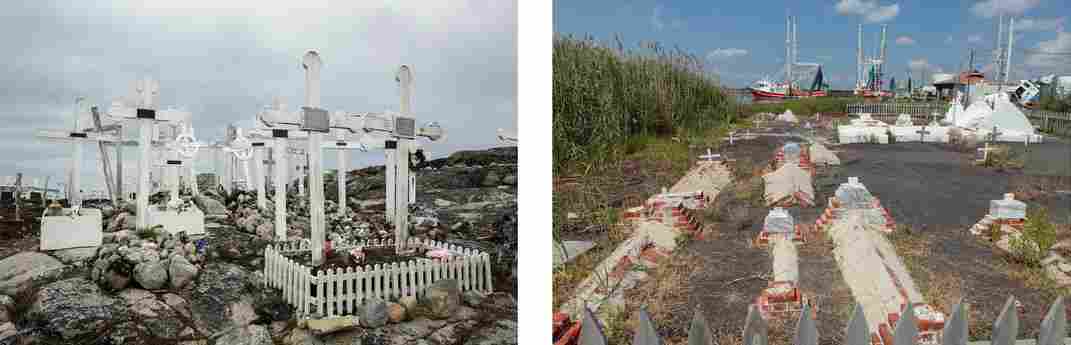

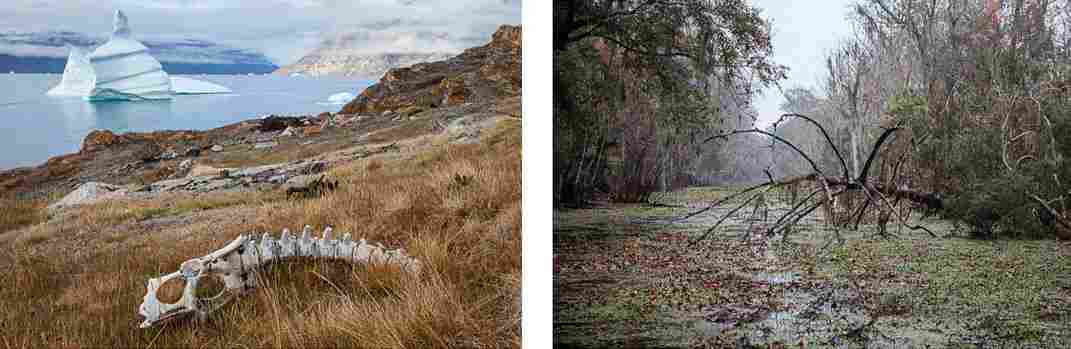

Photographer Tina Freeman draws attention to the interconnectedness of two far-flung landscapes—her home state of Louisiana and the glaciers at our planet's poles—in her show " Lamentations ," on view at the New Orleans Museum of Art through March 15, 2020. Over the course of seven years, she has captured both subjects, pairing photographs of Greenland’s permafrost, Iceland’s ice caves and Antarctica’s tabular ice sheets with visually similar images of Louisiana wetlands, the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and other coastal landscapes. The show features a selection of diptychs from her book of the same name that features 26 stunning image pairings.

“' Lamentations' profoundly engages with both its message and its messenger, with both the precarious existence of glaciers and wetlands and with photography itself,” says Russell Lord, NOMA’s curator of photographs, in a press release. “The diptychs introduce a series of urgent narratives about loss, in which the meaning of each individual image is framed, provoked, and even haunted by the other.”

Smithsonian magazine spoke with Freeman about her experience producing this compelling body of work.

How did this project begin? Where did you start shooting, and where did it take you?

I was given an opportunity to travel with 84 other photographers who were chartering a ship to Antarctica to photograph ice. It wasn't about the animals—just the ice. I went on this trip, and I came back with some amazing photographs. We were there early in the season and the ice was gorgeous. That's when I started looking for reasons to go to other places to photograph ice.

Later I went to Iceland—I became completely besotted by Iceland. Then I was in Spitsbergen, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. In Greenland, I've been to the east and the west coast—to the Scoresby Sound, the fjord system on Greenland’s East Coast. Then I went to the Jakobshavn glacier, which is at Ilulissat in Western Greenland.

When did it click for you to start pairing photos of ice with pictures of wetlands?

The pairing didn’t start right away. I’ve been surrounded by the wetlands all my life, but I hadn't really seen them as a photographer. When I was shooting the ice, I started seeing structural connections in these two different environments. After the first trip to Antarctica, I was invited to a New Year's Eve party at a duck camp on Avoca Island off the intercoastal waterway near Morgan City, Louisiana. The next morning on New Year's Day, we went out in a boat. It was an incredibly beautiful day—it was misting, and it was very gray. And that's when I started photographing the wetlands and when I started thinking about pairing these images.

The first pair was two horizontal images—one of the tabular icebergs in Antarctica and one of cypress trees in Louisiana. And then I started seeing more pairs that had some sort of similarity like a color—the pink and the orange of a sunset in Antarctica next to the orange booms from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. There were some other ones that had strong structural similarities too.

I started sending my digital files to Costco and printing out packs of drugstore-size, 4-by-6-inch images. I printed out hundreds of photos and started matching them. I have a wall with magnetic paint, so I put them up on the wall with magnets as pairs. And then I'd move around the pairs again; there are some images that have three or more really strong possible pairs. I can't tell you how much time I spent pairing. But once you do a lot of that you begin to go "Oh!" You'll see something new, and you'll go "Oh, I do have an image that will go with that."

How did you capture the different locations featured in this project?

Some of the earliest photographs were taken in 2006. So, obviously, they weren't initially intended for this project. At the time, another photographer and I decided to take as many day trips as we could outside of New Orleans to see the damage from Katrina. We would go as far as we could in a day. One of the images from that was of the oil tanks and another one was the white tombs in the Leeville cemetery in Louisiana that are all strewn about and piled on top of each other after Hurricane Katrina. A lot of the wetland images are from Avoca Island. The areas, like Avoca, that are vulnerable to sea level rise are very flat and unless you have any altitude, meaning the aerial photographs, they're not very interesting—whereas in Antarctica, you may see mountains on the horizon. Capturing the clouds on the horizon is really important when you're shooting in the wetlands here to add dimension.

But that's when I started shooting aerial photography with South Wings aviation , which is a group of volunteer pilots that give their time to bring people like the press, politicians and photographers to see what's going on with the environment from above. When I was flying, I knew there were certain areas that I wanted to look for, many from my childhood, like the South Pass Lighthouse near Port Eads. I could see what had changed—the rivers narrowed because the wetlands vanished, so the river is full of silt.

Have you always found yourself moved by climate change or other ecological disasters, or nature generally? How did it feel to create these pairings?

More than a decade ago, I was on a national conservation committee, and I wrote reports about environmental topics, including toxins and air quality, endangered species, climate change, plants and national forests. So I was really, really aware. Also, around that time, the Larsen-B ice shelf in the Antarctic Peninsula broke off in 2002. There was plenty of pretty high-profile stuff happening, if one was paying attention. I can't even tell you when I first became aware of all of this. Maybe it was with Hurricane Camille in 1969. My parents and my grandparents owned a piece of property in Mississippi, and it was quite impacted by Camille’s storm surge. We lost the house, so I was very aware of what storms were doing. One of the barrier islands near there broke in half when I was 19 years old. So the power of the environment has been a part of my life for a long time.

Talk about the name ‘Lamentations.’

It was a really hard one to come up with the right name. One of my first picks was ‘Doomsday,’ which was too over the top. And then I went with ‘Lost’ for a while and that didn't really cut it. ‘Lamentations’ is the best I could come up with—it brings forth the poetry and beauty. For me, photography is about beauty. I'm not into ugly scenes, it's not my thing. I want to seduce people with the beauty of what they're seeing, and then hopefully they'll take a closer look and learn more about what's happening.

Consider This Maverick of the Aesthetic Movement

The Smithsonian’s American Women’s History Initiative (“Because of Her Story”) asks us to consider the stories of notable figures in our history whose achievements have not always received the full appreciation they merit. October is the birth month of one such hidden figure, American artist Maria Oakey Dewing , who was born in New York City on October 27, 1845, a year before the Smithsonian Institution was founded. Her rare and wondrous Garden in May is one of the treasures of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Dewing described herself as a “garden-thirsty soul,” and Garden in May , the largest extant outdoor flower painting by the artist, certainly quenches that thirst, while also offering some food for the soul.

The painting is a total immersion into Dewing’s New Hampshire garden. There is no horizon, hardly a hint of ground, and no lateral framing to this sea of soft hues and dark leaves and stems. It is “all-over” painting decades before the advent of Abstract Expressionism. Much of the color is kept to the surface of the canvas, and while there is little sense of space, the rich textural depth of the drifts of plants and their manner of growth are strikingly evoked. If there is a point of view, it is that of the gardener, on her knees, using her expert hands to untangle the dense greenery. All seems mysterious and uncomposed, a shivering, restless environment filled with sprays of flowers. The artist creates a muted symphony of envelopment for the viewer, bowing and blowing in the wind. There is almost a feeling of being underwater, subject to rhythmic eddies and currents. Dewing wrote about the individual flower as the ultimate abstraction. Here, grouped together, the luminous blossoms offer the possibility of pure self-loss amid the layered shadows.

The small number of paintings by Dewing that have come down to us hovers around two dozen. Why so few? Many have been lost, but many more were simply never painted. In her 20s as an art student, Dewing was known as a maverick of the aesthetic movement, an avant-garde thinker and progressive author, one of the most promising painters of her generation. However, upon her marriage to fellow artist Thomas Wilmer Dewing in 1881, her artistic production more or less ceased for decades while she took on the domestic duties that her period expected of a wife and mother. This unequal, gender-based distribution of professional roles is common to a number of artistic couples in the nineteenth century. Still, while her oeuvre may be small, it is undeniably fervent. As Dewing is reported to have said to the writer Oscar Wilde, “I must paint pictures or die.”

John Davis is the Provost and Under Secretary for Museums, Education, and Research at the Smithsonian.

Celebrating the Eternal Legacy of Artist Yayoi Kusama

At first glance, the work of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama is visually dazzling. Her constructed boxed rooms with millions of reflections from strategically placed mirrors astonish all those who enter into them. Her brightly colored pumpkin sculptures loom larger-than-life in exhibitions and on Instagram feeds across the world. Packed with countless miniscule polka dots, her paintings create a sense of endlessness that challenges the borders of her canvas.

As if walking into a hallucination, it’s difficult to make sense of the repetitive motifs and endless spaces that feel so different from daily life. Self-described as the “modern Alice in Wonderland,” Kusama enthralls with these infinite visions; she generously welcomes museumgoers into a visualization of the world as she sees it.

Now 90 years old, Kusama was an active participant in the art world of the 1960s when she arrived in New York City from Kyoto in 1958. Growing up in an abusive household, Kusama, at the age of 10, began experiencing hallucinations. Dots, pumpkins and flashes of light occupied her vision. She later began to recreate these motifs through her art as a form of therapy.

Mental health issues prompted her to return to Tokyo and in 1977, she voluntarily checked herself into a mental institution. Today Kusama still lives in the institution, which is just down the street from her art studio. She travels back and forth between both locations and continues to create her signature pieces.

The idea that everything in our world is obliterated and comprised of infinite dots, from the human cell to the stars that make up the cosmic universe, is the theme of her art. As Kusama describes herself, “with just one polka dot, nothing can be achieved. In the universe, there is the sun, the moon, the earth, and hundreds of millions of stars. All of us live in the unfathomable mystery and infinitude of the universe.”

Attendees of the Hirshhorn’s immensely popular 2017 survey, “ Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors ” exhibiting six of Kusama’s Infinity Rooms, were able to experience this phenomenon for themselves.

It was a highly-anticipated moment in Kusama’s journey as an artist, and visitors responded, queuing up and waiting for hours to enter the museum to experience the otherworldly realms for themselves. The museum reports that nearly 160,000 people experienced the show, bumping its annual visitor record to 475,000.

Kusama channels recent cultural trends and technological advancements through her Infinity Rooms. This has allowed her to become one of the most famous artists of her generation and has kept her art relevant for decades. The spark in popularity of photography in the social media age aligns well with the self-reflection element of the Infinity Rooms.

“The self-envisioning that we see happening through social media today and through other forms of photography,” explains Betsy Johnson, a curator at the Hirshhorn, “is something that was a part of Kusama's practice the whole way through, but it just so happens that today that has become something that is at the forefront of our collective consciousness. It’s just the perfect fusion of cultural currents with something that was always a part of her practice.”

Now, the Hirshhorn announces yet another Kusama exhibition, “ One with Eternity: Kusama in the Hirshhorn Collection,” which opens in April. The show promises a tribute to the artist, rooting her otherworldly art within her life experiences. Kusama’s art is tied to overarching events she was experiencing at the time of their creation.

“She's become bigger than life, people look at artists and they think they're just special or different,” explains Johnson, who is organizing the upcoming exhibition. “One of the really wonderful things about working your way through a person's biography is understanding all of the little steps along the way that created what we see today.”

The objects on display will draw from different parts of her career, helping humanize the artist and deepen viewers’ appreciation of her work. While pumpkins, patterns and polka dots have been Kusama’s signature motifs, the artist has also experimented with other art forms that were influenced by her childhood. Among the five objects on display in this collection are some of her earliest paintings and photographs, as well as her 2016 signature sculpture titled Pumpkin and now held in the museum’s collections.

One piece from the collection, the 1964 Flowers—Overcoat is a gold coat covered with flowers. The sculpture reveals details of Kusama’s early life. “She wasn't always just focused on polka dots; she has this history where her family had acreage and grew plants,” Johnson says of the origin of Kusama’s interest in fashion. “This experience with organic forms is very much a part of her early practice and continues throughout her career.”

The exhibition will introduce the museum’s most recent acquisitions—two Infinity Mirror Rooms. A breakthrough moment in Kusama’s career was when she began constructing these experiential displays in 1965. No bigger than the size of small sheds , the interior of these rooms is lined with mirrored panels that create the illusion of endless repetition. Each room carries a distinct theme, with objects, sculptures, lights or even water reflected onto its mirrored walls.

The artist has constructed about 20 of these rooms, and has continued to release renditions up to this day. The evolution of these rooms demonstrates how her understanding of the immersive environment has shifted throughout the decades. On display at the upcoming exhibition will be Kusama’s first installation, Infinity Mirror Room—Phalli’s Field (Floor Show) (1965/2017) as well as one of her most recent rooms. The title and theme of the new room, newly acquired by the museum, is yet to be announced.

Johnson won’t say much about the museum’s newest Infinity Room acquisition but she did hint that in true Kusama fashion, the room feels otherworldly, seeming to exist outside of space and time.

The Discovery of the Lost Kusama Watercolors

Even at the beginning of her career, Kusama’s desire to understand her hallucinations and mediate her interaction with the world was expressed through her practice. Before transforming her visions into unique renditions of eternal repetition and perceptual experiences, Kusama expressed them through early paintings and works on paper.

The visual elements that Kusama audiences admire took Smithsonian archivist Anna Rimel quite by surprise late last year, when she was going through archived materials at the Joseph Cornell Study Center at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Rimel was conducting a preliminary survey of the Joseph Cornell papers when she found the paintings. Gathered in a worn manila envelope with Cornell’s writing on the outside were four previously undiscovered Kusama watercolors . The paintings were stored with their original receipts and given titles and signed by Kusama herself, making them an exciting discovery for Rimel and the museum staff.

“They're very ethereal looking. The images themselves seem to be emerging out of a murky background, they give off a very oceanic kind of quality,” says Rimel. “They're really visceral, you can't help but react to them when you see them.”

These watercolor works date back to the mid-50s, bordering Kusama’s transition from Japan and into the United States. They were purchased by artist Joseph Cornell, a friend and supporter of Kusama’s art.

Although different from the vibrant nature of her more recent pieces, these watercolor paintings share the cosmological nature Kusama would later expand on with the Infinity Rooms and other pieces. The watercolor paintings have been transferred to the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum .

As this recent discovery indicates, Kusama’s career is continuing to surprise art enthusiasts by offering up new gifts to admire. A tribute to her legacy, the upcoming Hirshhorn exhibition will celebrate the artist whose work has now become a part of the Institution's history.

“The Kusama show was huge for us in so many ways and really helped draw a larger audience, and we really recognize that,” Johnson says. “As a result of that, we really want to continue her legacy in D.C., and in our museum,”

In 1968, in an open letter to then-president Richard Nixon, Kusama wrote , “let’s forget ourselves, dearest Richard, and become one with the absolute, all together in the alltogether.” Loosely derived from these words, Johnson named the exhibition, “One with Eternity” in reference to the museum's effort to ensure that the artist’s legacy, like her art, becomes eternal.

“That's what museums are in the practice of doing—making sure that an artist's legacy lasts for as long as it possibly can,” explains Johnson. “It’s about making sure that this legacy that she has created is sustained into the future.”

Currently, to support the effort to contain the spread of COVID-19, all Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.C. and in New York City, as well as the National Zoo, are temporarily closed. Check listings for updates. The the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden has postponed the opening of “One with Eternity: Kusama in the Hirshhorn Collection ” until later in the year. Free same-day timed passes will be required for this experience and will be distributed daily at the museum throughout the run of the exhibition.