In 1904, the priest of the Gentle Sky clan, Shonke Mon-thi^ , came to Washington, D.C. as a member of an Osage delegation to negotiate the land and mineral rights of his nation. While in this city of diplomatic exchanges, the clan leader received an invitation from the Smithsonian Institution’s U.S. National Museum to pose for a photographer and have a plaster life mask made of his face.

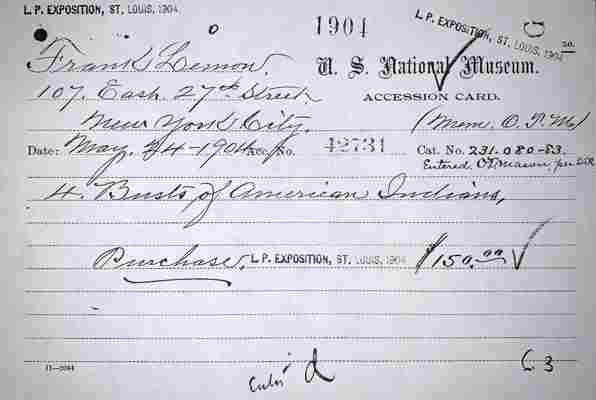

The resulting photographs and plaster were collected by the museum’s department of anthropology. They also served as the basis for sculptor Frank Lemon , who used them to craft a polychrome plaster bust that was exhibited at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri. The fair’s extensive anthropological and ethnographic exhibits were widely varied, featuring busts, musical instruments, textiles, baskets, a model American Indian boarding school and numerous native villages with close to 3,000 indigenous people from North America and other parts of the world.

The St. Louis anthropological exhibitions, according to the U.S. National Museum’s annual report, were designed to illustrate the “higher culture of the Native American peoples as shown in their arts and industries.” The fair’s central topic of focus, however,—industrial and technological progress—created a symbolic contrast. Scholars Nancy J. Parezo and Don D. Fowler explore in depth the anthropologic exhibitions of the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition and the ideas on race that it promulgated. According to their book Anthropology Goes to the Fair: The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exhibition , the displays helped to foster a divide between the natives as representatives of so-called “primitive” societies, and the fair’s urban, middle and upper class, Euro-American audiences, as emblematic of “civilized” Americans.

In 2014, Latino artist Ken Gonzales-Day , while studying on a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, was exploring the anthropology collections at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and came across Lemon’s 116-year-old sculpture of Shonke Mon-thi^.

Gonzales-Day’s research and the recent acquisition of one of the artist’s photographs into the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery represents a new approach to bringing acknowledgment and honor to one of the most decorated of Osage warriors and helps the museum to present a more inclusive view of American history. The story of how it happened and the process involved is a fascinating one.

“When I first saw Shonke Mon-thi^ ’s bust,” says Gonzales-Day, “I felt certain he was a man of importance. He had been painted with great care and unlike some other works in the collection, his name appeared on the plinth.” The polychrome bust depicts an elder man with a stern expression; his hair is shaved on the sides while locks fall to his neck. The sculpture is chipped at various places, the white plaster breaking through the subject’s brown skin evokes the age of the object itself.

“I thought perhaps it was part of a group of works I had been searching for, that had been displayed as part of the Louisiana Purchase International Exposition,” says Gonzales-Day. “It was. So not only was he a man of importance to his people, his likeness was also presented to exposition goers, and as such, he clearly represented a missing piece from the history of racial formation in the United States.”

A case in point was the outcome of our research around the portrait of Shonke Mon-thi^. After months of looking for clues by cross-referencing sources with different spellings, we finally understood the stature of the sitter in his community and his contributions to the United States.

Shonke Mon-thi^ is often referred to as Shunkahmolah , his birth date is unknown, his death date is believed to be around 1919. He was a spiritual and political leader of the Osage Nation and won honors during an attack on Confederate forces in 1863. By the time of his death, Shonke Mon-thi^ was one of three living men who had earned all 13 o-don, or war honors, given unanimously by his nation. In addition, he assisted Smithsonian anthropologist Francis La Flesche , a member of the Omaha Tribe, in documenting Osage religious rites. The details of the subject’s life, including his participation in the Osage delegation to Washington, D.C., in 1904, made clear his historical significance. The Portrait Gallery’s curatorial committee agreed with this conclusion, so I reached out to representatives of the Osage Nation and asked if they would support the Portrait Gallery’s acquisition of Gonzales-Day’s related photograph.

I subsequently made contact with Steven Pratt, great grandson of Shunkahmolah, who received the idea enthusiastically and provided additional details on the biography of his great grandfather. I learned that Shonke Mon-thi^ (“Walking Dog”) earned his name for his remarkable ability to run long distances carrying messages between Osage chiefs. Anglo-Americans, unable to pronounce his name, had started calling him Shunkamolah.

Pratt supported the acquisition but asked that the title of the sculpture be changed to his great grandfather’s original name. With the approval of the Osage and the Traditional Cultural Advisors Committee, as well as that of the National Portrait Gallery’s Board of Commissioners, Gonzales-Day’s photograph of the Portrait of Shonke Mon-thi^ entered the museum’s collections this past summer. To complete the circle, Gonzales-Day gifted a print of the photograph to Steven Pratt, as a gesture of respect for the living legacy of his ancestor.

Once the process of acquisition had ended, I could not help but marvel at the remarkable turn of events this acquisition embodied. A major political and spiritual Osage leader and warrior had claimed his rightful place in the nation’s Portrait Gallery.

Thanks to the vision of one contemporary artist, who through his camera lens reframed an anthropological bust as a memorializing portrait, and after the constructive dialogue between Native stakeholders and museum professionals, Shonke Mon-thi^’s visual biography now resides in a national collection dedicated to the individuals who have shaped America’s history and culture.

I would like to thank Gwyneira Isaac , curator of North American Ethnology at the National Museum of Natural History, for her valuable insight into the history of anthropological busts, casts and the development of theories on race. Thanks as well to Larry Taylor, a pivotal figure in the rediscovery of Native American face casts in museum collections, for sharing his knowledge of Shonke Mon-thi^ and the sculptures known as the "Osage Ten." Finally, my deep gratitude goes to Steven Pratt, the great grandson of Shonke Mon-thi^, Andrea Hunter, director of the Osage Tribal Historic Preservation Office, and the Traditional Cultural Advisors, for their counsel and trust in the process of representing Shonke Mon-thi^ at the National Portrait Gallery.

How American Brewers Employed Fine Art to Sell Beer

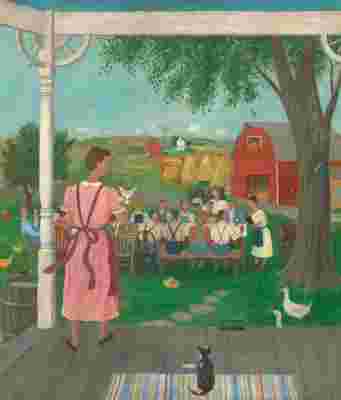

It would be easy to mistake the painting Harvest Time for an uncomplicated image of Midwestern bliss, a picture of ease and plenty after a hard day’s work. It is an unassuming portrayal of a picnic in rural Kansas, with a group of farm workers gathered congenially around a table, drinking beer and laughing. The sun is shining, the hay is piled high and friendly barnyard animals roam over lush green grass. In fact, Harvest Time was created with a specific goal: to convince American women to buy beer.

It was 1945 and the United States Brewers Foundation, an advocacy group for the beer industry, sought out the artist, Doris Lee, to paint something for an advertising campaign they called “Beer Belongs.” The ads, which ran in popular women’s magazines like McCall’s and Collier’s featured works of art that equated beer drinking with scenes of wholesome American life. The artworks positioned beer as a natural beverage to serve and to drink in the home.

“Lee was one of the most prominent American women artists in the 1930s and the 1940s,” says Virginia Mecklenburg, chief curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, where Lee’s Harvest Time can be seen on the museum’s first floor. The artwork is featured in the next episode of “Re:Frame,” a new video web series, that explores art and the history of art via the lens of the vast expertise housed at the Smithsonian Institution.

Born in 1905 in Aledo, Illinois, Lee was celebrated for her images of small-town life. She was known for portraying the simple pleasures of rural America—family gatherings, holiday meals, the goings-on of the country store—with thoughtful and sincere detail. She “painted what she knew, and what she knew was the American Midwest, the Great Plains states, the farmlands near where she had grown up,” says Mecklenburg.

For American women, negative perceptions of beer began as early as the mid-1800’s. “Really, from the mid-19th-century, into the 20th-century, beer came to be associated with the working man, who was drinking outside of the home at a saloon or a tavern, and that was a problematic factor of the identity of beer that helped lead to Prohibition,” says Theresa McCulla , the Smithsonian’s beer historian, who is documenting the industry as part of the American Brewing History Initiative for the National Museum of American History.

Prohibition, the 13-year period when the United States banned the production, transportation and sale of alcoholic beverages, cemented the perception among women that beer was an immoral drink. “When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, brewers had a bit of a challenge ahead of them,” says McCulla. “They felt like they really needed to rehabilitate their image to the American public. They almost needed to reintroduce themselves to American consumers.”

“In the 1930's, going into... the war era leading up to 1945, you see a concentrated campaign among brewers to create this image of beer as healthful and an intrinsic component of the American diet, something that was essential to the family table,” she says.

The Brewers Foundation wanted to reposition beer as a central part of American home life. According to the advertising agency J. Walter Thompson, who created the “Beer Belongs” campaign: “The home is the ultimate proving ground for any product. Once accepted in the home, it becomes part of established ways of living.” And in the mid-1940s, American home life was squarely the realm of women. The smart incorporation of fine art into the campaign added a level of distinction and civility. Viewers were even invited to write to the United States Brewers Foundation for reprints of the artworks “suitable for framing,” subtly declaring the advertisements—and beer by association–appropriate for the home.

“Women were important, intrinsic to the brewing industry, but really for managing the purse strings,” says McCulla, “women were present as shoppers, and also very clearly as the figures in the household who served beer to men.”

Doris Lee imbued her work with a sense of nostalgia, an emotion that appealed to the United States Brewers Foundation when they conceived of the “Beer Belongs” campaign. “Even though many Americans at this time were moving from rural into urban areas, brewers often drew on scenes of rural life, as this kind of authentic, wholesome root of American culture, of which beer was a crucial part,” says McCulla.

As a woman, Doris Lee’s participation legitimated the campaign. The advertisement blithely pronounced: “In this America of tolerance and good humor, of neighborliness and pleasant living, perhaps no beverage more fittingly belongs than wholesome beer, and the right to enjoy this beverage of moderation, this too, is part of our own American heritage or personal freedom.”

Though women weren’t considered the primary drinkers, their perception of beer was the driving force in making it socially acceptable in the wake of Prohibition. Using artworks like Harvest Time the “Beer Belongs” campaign cleverly equated beer drinking with American home life, breaking down the stigma previously associated with the brew.

The United States Brewers Foundation succeeded in changing American perceptions of beer. Today, beer is the most popular alcoholic beverage in the United States , with per capita consumption measured in 2010 at 20.8 gallons a year.

Doris Lee's 1945 Harvest Time is on view on the first floor, south wing of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

Here’s Why A.I. Can’t Be Taken at Face Value

At a moment when civil rights groups are protesting Amazon’s offering its face-matching service Rekognition to the police, and Chinese authorities are using surveillance cameras in Hong Kong to try to arrest pro-democracy campaigners, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum offers a new show that could not be more timely.

The exhibition, “Face Values: Exploring Artificial Intelligence,” is the New York iteration of a show the museum organized, as the official representative of the United States, for the 2018 London Design Biennial . It includes original works the museum commissioned from three Americans, R. Luke DuBois , Jessica Helfand , Zachary Lieberman as well as a new interactive video experience about AI by the London filmmaker Karen Palmer of ThoughtWorks. The imaginative installation, which includes a screen set into a wall of ceiling-high metal cat tails, was designed by Matter Architecture Practice of Brooklyn, New York.

“We are trying to show that artificial intelligence is not all that accurate, that technology has bias,” says the museum’s Ellen Lupton , senior curator of contemporary design.

R. Luke DuBois’s installation, Expression Portrait , for example, invites a museumgoer to sit in front of a computer and display an emotion, such as anger or joy, on his or her face. A camera records the visitor’s expression and employs software tools to judge the sitter’s age, sex, gender and emotional state. (No identifying data is collected and the images are not shared.) We learn that such systems often make mistakes when interpreting facial data.

“Emotion is culturally coded,” says DuBois. “To say that open eyes and raised corners of the mouth imply happiness is a gross oversimplification.”

DuBois wants the viewer to experience the limits of A.I. in real time. He explains that systems often used in business or governmental surveillance can make mistakes because they have built-in biases. They are “learning” from databases of images of certain, limited populations but not others. Typically, the systems work best on white males but less for so just about everybody else.

Machine-learning algorithms normally seek patterns from large collections of images—but not always. To calculate emotion for Expression Portrait , DuBois used the Ryerson Audio-Visual Database of Speech and Song (RAVDESS) , which is comprised of video files of 24 young, mostly white, drama students, as well as AffectNet , which includes celebrity portraits and stock photos. DuBois also used the IMDB-WIKI dataset , which relies on photos of famous people, to calculate people's age. Knowing the sources of Dubois’s image bank and how databases can be biased makes it easy to see how digital systems can produced flawed results.

DuBois is director of the Brooklyn Experimental Media Center at New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering. He trained as a composer and works as a performer and conceptual artist. He combines art, music and technology to foster greater understanding of the societal implications of new technologies.

He is certainly on to something.

Last week the creators of ImageNet, the 10-year-old database used for facial recognition training of A.I. machine learning technologies, announced the removal of more than 600,000 photos from its system. The company admitted it pulled millions of photos in its database from the Internet, and then hired 50,000 low-paid workers to attach labels to the images. These labels included offensive, bizarre words like enchantress, rapist, slut, Negroid and criminal. After being exposed, the company issued a statement : “As AI technology advances from research lab curiosities into people’s daily lives, ensuring that AI systems produce appropriate and fair results has become an important scientific question.”

Zachary Lieberman, a New Media artist based in New York, created Expression Mirror for the Cooper Hewitt show. He invites the visitor to use his or her own face in conjunction with a computer, camera and screen. He has created software that maps 68 landmarks on the visitor’s face. He mixes fragments of the facial expression of the viewer with those of previous visitors, combining the fragments to produce unique combined portraits.

“It matches the facial expression with that of previous visitors, so if the visitor frowns, he or she sees other faces with frowns,” Lieberman says. “The visitor sees his expression of an emotion through those on other people’s faces. As you interact you are creating content for the next visitor.”

“He shows it can be fun to be playful with data,” Lupton says. “The software can ID your emotional state. In my case, it reported I was 90 percent happy and 10 percent sad. What is scary is when the computer confuses happy and sad. It’s evidence the technology is imperfect even though we put our trust in it.”

Lieberman c0-founded openFrameworks , a tool for creative coding, and is a founder of the School for Poetic Computation in New York. He helped create EyeWriter, an eye-tracking device designed for the paralyzed. In his Expression Mirror , white lines produce an abstract, graphic interpretation of the viewer’s emotional status. “If you look happy you might see white lines coming out of your mouth, based on how the computer is reading your expression, ” he says.

Jessica Helfand, a designer, critic, historian and a founder of the blog and website “Design Observer,” has contributed a visual essay (and soundtrack) for the show on the long history of facial profiling and racial stereotyping titled A History of Facial Measurement .

“It’s a history of the face as a source of data,” Lupton says. Helfand tracks how past and present scientists, criminologists and even beauty experts have tried to quantify and interpret the human face, often in the belief that moral character can be determined by facial features.

Karen Palmer, the black British filmmaker, calls herself a “Storyteller from the Future.” For the show, she created Perception IO (Input Output) , a reality simulator film.

The visitor takes the position of a police officer watching a training video that portrays a volatile, fraught scene. A person is running toward him and he tries to de-escalate the situation. How the visitor responds has consequences. A defensive stance leads to one response from the officer, while a calm, unthreatening one leads to a different response.

Perception IO tracks eye movements and facial expressions. Thus, the visitor is able to see his or her own implicit bias in the situation. If you are a white policeman and the “suspect” is black, do you respond differently? And visa versa. Palmer’s goal is for viewers to see how perceptions of reality have real-life consequences.

The takeaway from the show?

“We need to understand better what A.I. is and that it’s created by human beings who use data that human beings select,” Lupton says. “Our aim it to demystify it, show how it’s made.”

And the show is also meant to be entertaining: “We are trying to show what the computer thinks you are.”

“Face Values: Exploring Artificial Intelligence,” is on view at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City through May 17, 2020. The museum is located at 2 East 91st Street (between 5th and Madison Avenues.