When the Korean artist Lee Ufan was first commissioned to do a site-specific exhibition in the plaza of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden two years ago, he came to Washington, D.C. see what he would be dealing with.

The museum, itself designed as a “large piece of functional sculpture” by the renowned architect Gordon Bunshaft in the 1960s, is centered on a large 4.3-acre plaza on the National Mall. There surrounding the cylindrical building, works of art are displayed outdoors and year-round in the quiet recesses and grassy nooks of the walled plaza.

Now for the first time in the Hirshhorn’s 44-year history, curators have relocated or stored the artworks on the museum’s plaza and devoted the space, almost in its entirety, to a single artist.

Lee, 83, a leading voice of Japan’s avant-garde Mono-ha movement , meaning “School of Things,” has exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2007, the Guggenheim Museum in 2011 and the Palace of Versailles in 2014. But the artist who is a painter, sculptor, poet and writer, as well as part philosopher, sees his contributions as the finishing of a dialogue begun by the spaces in which he works. “By limiting one’s self to the minimum,” he has written , “one allows the maximum interaction with the world.”

To create his distinctive, sleek sculptures, the artist brought tons of rock and steel to Washington D.C. But as he said while walking around the ten creations a week before the opening of his exhibition, “Not important, object. Space is more important.”

So in front of a piece on the plaza’s southeast corner with a nearly 20-foot-high vertical silver needle, a steel circle on the ground and two large stones in a field of white gravel that replaces the museum’s grass, the artist explains, because “tension is what I needed.” That helped define the space “because of this gravel and steel, my choice.”

Like every one of his sculptures, it has the title Relatum , to refer to the relations of objects to their surroundings, to each other, and to the viewer. Each work in the series also has a subtitle, and this one, Horizontal and Vertical, refers to the gleaming needle. The piece is now standing at the point where the soaring aluminum tubes and stainless-steel wires of Kenneth Snelson’s Needle Tower long reigned.

Lee’s work is just as defining of the space, while it also echoes the strong vertical of an industrial crane that happens to soar over the National Air and Space Museum, which is undergoing a major renovation across 7th Street. The artist waves this off as a coincidence.

“A plain, natural stone, a steel plate . . . and existing space are arranged in a simple, organic fashion,” Lee once wrote. “Through my planning and the dynamic relationships between these elements, a scene is created in which opposition and acceptance are intertwined.”

The Hirshhorn exhibition, “Open Dimension,” curated by Anne Reeve , is Lee’s largest outdoor sculpture installation of new work in the U.S. It is accompanied by a complementary installation on the museum's third floor of four of Lee’s Dialogue paintings from the past four years, where clouds of color float on white or untreated canvas.

Lee’s takeover required moving or storing familiar plaza sculptures. Yayoi Kusama’s Pumpkin was transferred to the museum’s sculpture garden across the street; and Roy Lichtenstein’s Brushstroke is on loan to the Kennedy Center’s new performance spaces known as The REACH , but Jimmie Dunham’s sculpture Still Life with Spirit and Xitle , installed in 2016, remains. The work mirrors Lee’s with its use of stone—a nine-ton volcanic boulder (with a smile on its face) crushes a 1992 Chrysler Spirit.

Lee’s work is more sleek. With his Relatum—Open Corner elegantly reflecting the curves in the alcoves of Bunshaft’s Brutalist building; his Relatum—Step by Step has the step climbing a couple of stairs with curling stainless steel.

In another alcove, a shiny piece of stainless steel on its edge curls inward, allowing a visitor to enter and be alone in the center swirl. “It’s kind of like a hall of mirrors,” Lee says to me through a translator. “You’re going to get a little bit disoriented.” Is it meant to be one of those big, rusting spirals by Richard Serra that similarly swallow viewers?

“Not same idea,” Lee says. “Big difference for me.” But, he adds, “Serra is very old friend. First time I met him was in 1970 in Tokyo. He and I were in the same gallery in Germany.”

The works with white gravel especially suggest the quiet grace of a Japanese rock garden, other works with stainless steel bases are placed on the grass, which continue to be watered in the dry autumn. “It’s a problem,” he says. Rivulets from a sprinkler on Relatum—Position, later turned to orange stains in the late afternoon sun.

He plays with the sun and shadow in a two-rock piece called Relatum—Dialogue , in which two boulders placed near one another have their morning shadows painted black on the white gravel (causing two different shadows most of the day, aside from the one moment when they align).

Despite the title, one rock seems to be turning away. “It’s supposed to be a dialogue,” Lee says, “but his mind is different.” Asked if he was trying to depict the kind of ideological division familiar in Washington D.C. within sight of the U.S. Capitol, Lee just laughs.

Some of the work did reflect the city, however. Lee says he admires Washington’s clean layout, compared to the bustle of New York City. “Here, very quiet, very smooth, very slow,” Lee says. “New York is a big difference.” So, Lee created his own pool, a square with two rocks, four sheets of shiny stainless steel and water called Relatum—Box Garden , with only the wind creating ripples on its still, reflecting surface. The work is placed between the Jefferson Drive entrance from the Sculpture Garden and the Bunshaft-created fountain, now working again following two years of repair work.

The centerpiece of the plaza is the fountain, which is also a main focus of Lee’s exhibition. Eleven curved steel pieces—mirrored on one side, are placed in a kind of maze, allowing for two entrances. Once in, a viewer can see how the addition of black ink to the water better reflects the blue sky and the curves of the building above (though the coloring gives a greenish tint to the water spouting at the center of the fountain).

Lee was vexed by the heavy concrete boxes in some of the sculpture spaces that were originally meant to hold landscaping lights, though one of these didn’t seem to infringe much on the steel circles and stone placements in Relatum—Ring and Stone .

The museum wants to keep visitors off the white gravel, though they can approach the works on the grass. Signs all over ask that visitors not touch or climb on the art works—even though Lee subtitles the work Come In.

Lee says the many annual visitors of the Hirshhorn—numbering 880,000 last year—needn’t have a deep understanding of conceptual art to get something out of it. “ Experience is more important; not meaning,” he says. “My work has some meaning, but more important is pure experience.” Just then, a passerby noticing the artist stopped him in the plaza. “We wanted to tell you how beautiful it is,” she said.

“ Lee Ufan: Open Dimension” continues through September 12, 2020 at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C.

As African Art Thrives, Museums Grapple With Legacy of Colonialism

In 1897, 1,200 British troops captured and burned Benin City. It marked the end of independence for the Kingdom of Benin, which was in the modern-day Edo state in southern Nigeria. In addition to razing the city, British troops looted thousands of pieces of priceless and culturally significant art, known as the Benin bronzes.

More than a century later, the museums that house these pieces are grappling with the legacy of colonialism. Leaders in Africa have continued their call to get the Benin bronzes and other works of art taken by colonists back, at the same time as new museums open up across Africa. (In 2017, the Smithsonian's National Museum of African Art organized its first traveling exhibition in Africa showcasing the work of the Nigerian photographer Chief S. O. Alonge. The show, catalogue and educational program were organized and produced in partnership with Nigeria's national museum in Benin City. Alonge was the official photographer to the Royal Court of Benin.)

The British Museum, which has the largest collection of Benin bronzes, is in communication with Nigeria about returning the bronzes. They’re waiting for the completion of the Benin Royal Museum, a project planned for Benin City. Edo state officials recently tapped architect David Adjaye, who designed the National Museum of African American History and Culture, to do a feasibility study on the site.

Additionally, Nigeria’s first privately funded university museum opened at the Pan-Atlantic University east of Lagos in October thanks to a large donation from Yoruba Prince Yemisi Shyllon, Smithsonian’s Charlotte Ashamu pointed out at a panel on the problems facing Africa’s museum sector last month.

Ashamu grew up in Lagos and is now an associate director at the African Art Museum. The panel was part of a Global Consortium for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage symposium co-hosted by Yale University and the Smithsonian Institution and organized by the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. Ashamu says the opening of new museums in Africa, like Shyllon’s, is of significant importance.

“It’s changing the narrative that I hear often in the United States, and that’s the narrative that Africans can’t pay or don’t have resources to support their own cultural sector,” Ashamu says. “There are plenty of resources. There is wealth, and it is being invested in the museum and cultural sector.”

Ashamu says Shyllon’s museum is just one example of many new, similar projects across Africa where personal wealth is being invested in the arts.

But Athman Hussein, the assistant director of the National Museums of Kenya , says that private investments alone won’t get many of the public museums in Kenya to the place they need to be to handle large collections of repatriated objects.

He says a lack of funding from the state has made it hard to even keep lights and air conditioning on in some museums.

“You cannot sugar-coat issues,” Hussein says. “If you go to a doctor, or in this case a consortium . . . you have to speak to what is ailing.”

Plus, Hussein says there are other obstacles facing the continent’s cultural heritage sector, like security. He says in Kenya, increasing security threats mean dwindling tourism numbers, which further impacts attendance at museums. Several panelists at the event expressed the importance of not sticking solely to traditional, Western models of museums. Ashamu says African museums need to start looking into “innovative business models.”

That’s just what Uganda’s Kampala Biennale is aiming to do. The group pairs emerging Ugandan artists with experienced artists for mentorships to empower and teach a new generation of artists in the country. They also host arts festivals around Uganda.

The Biennale’s director, Daudi Karungi , says that the idea of brick-and-mortar museums are less important to him than arts education and creating culturally relevant spaces for art and history. In fact, he says the museum of the future he’d like to see in Uganda wouldn’t look much like what museum-goers in the West are used to.

“Our museum, if it ever happens … it will be one of free entrance, it’ll have no opening or closing times, the community where it is will be the guides and the keepers of the objects, it should be in rooms, outdoors, in homes, on the streets,” Karungi says. “It should not be called a museum, because of course a museum is what we know. So this new thing has to be something else.”

The Smithsonian Institution is also exploring new ways to get objects back into the communities they come from. For example, the National Museum of Natural History’s Repatriation Office teamed up with the Tlingit Kiks.ádi clan in Southeast Alaska to create a reproduction of a sacred hat that had entered the museum's collections in 1884 but was too badly broken to be worn in clan ceremonies. The 3-D hat, dedicated in a ceremony earlier this fall, represented a new form of cultural restoration using digitization and replication technology to go beyond restoration.

Michael Atwood Mason , director of the Smithsonian Folklife and Cultural Heritage , points out that the University of British Columbia's Museum of Anthropology is also making short-term loans so pieces of indigenous art can spend time closer to the communities where they’re from.

“Many of us recognize that there is a historical imbalance in relationships, and we’re seeking ways to ameliorate that,” Mason says.

“There is a huge territory for us to explore in terms of potential collaboration,” says Gus Casely-Hayford , director of the African Art Museum. But for now, he says their first goal is on other kinds of partnerships to benefit Africa’s museum sector, like conservation and curation training.

Some panelists say it might be a long road for many of Africa’s museums before they’re ready to get back some of the larger or more delicate collections. Casely-Hayford says one Smithsonian study found that the vast majority of museums in Africa don’t feel they have the resources to tell their own stories in the way they’d like.

But Casely-Hayford, who recently announced he is leaving the Smithsonian to head the Victoria & Albert East in London, says going down that road is crucial for the future.

“Culture is essentially defining what we are, where we’ve been and where we might be going,” he says. “And I just think in Africa, the continent in this very moment is on the cusp of true greatness. Culture must be absolutely part of its nations’ narratives.”

John Baldessari: An Appreciation

One of the giants of American art, both literally and figuratively, John Baldessari passed away just after the new year, on January 2, 2020. He was six foot, seven inches tall, had more than 200 solo exhibitions in his lifetime, and was a formative teacher to generations of aspiring artists from the 1970s until the 2000s. (For a super quick, super fun summary of his life, work, and sensibility, check out this video made when LACMA honored him in 2011 ).

At the Smithsonian American Art Museum, we have four videos from the 1970s by Baldessari in our collection , as well as a multi-part print piece from the 1980s. Each in its own way suggests the playful, pedagogical approach he took to looking, thinking, and creating as well as the recurring sources of inspiration within his practice.

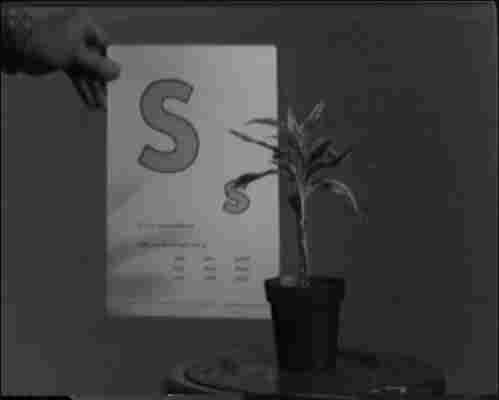

In the 1972 video, Teaching a Plant the Alphabet , a static camera shot opens on a humble potted houseplant. It sits on a table with a nondescript brick wall behind it. After almost thirty seconds of silence and stillness, a hand holding a paper printed with “A”, “a” and several small words (likely starting with the letter A but hard to read), enters the frame from the left. At the same time, a man’s voice starts intoning “aaayy, aaayy, aaaayy…” for another thirty-odd seconds. Then the hand and paper are withdrawn, there is a pause, and the same sequence is repeated, instructing the plant on the sounds, shapes and uses of the letters B through Z. This takes approximately eighteen minutes. After a final long pause, the sound cuts out and the tape ends. Described as a “rather perverse exercise in futility,” this piece is also a perfect introduction to Baldessari. The banality turns in on itself and the viewer becomes transfixed by the artists unwavering commitment to this thankless task. The droll, uninflected presentation becomes a humorously literal exploration of complex theories about how meaning adheres to abstract shapes and sounds to form language. And finally, it emphasizes teaching and language as imperfect modes of transmission and translation that, nevertheless, shape how we engage and understand the world around us. As Baldessari himself noted, “When I think I’m teaching, I’m probably not…When I don’t think I’m teaching, I probably am.”

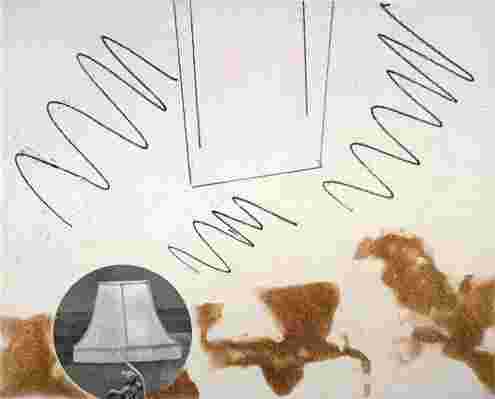

In the subsequent years, language, teaching, and the relationship between images and ideas would remain central to Baldessari’s practice. Two later works in our collection show how this interest intersected with film and pop culture—in the 1973 video Ed Henderson Reconstructs Movie Scenarios , Baldessari asks his student to looks at stills taken from obscure movies, and imagine what the films might be about. As you watch, you are likely to find yourself playing along—and realizing how much inference comes not just from what is in the picture, but from cultural tropes learned over years of watching Hollywood films and seeing certain characters and stories told over and over. Baldessari’s Black Dice from 1982 takes up this game in print form, slicing a still image from a gangster movie into nine parts. Each of these sheets is somewhat abstracted but with visual clues remaining. The viewer is encourage to try to reassemble them in their mind and extrapolate a narrative from there—Baldessari instructs the museum to display the original photograph alongside the prints, presumably to help viewers puzzle this out.

Shortly after this, in 1985, Baldessari struck on what would be the most visually iconic strategy in his work—affixing bright colored circular stickers onto photocollages to obscure the faces of the actors, so their identities wouldn’t be the focus of the composition. These experiments would quickly grow, forming the basis for monumental, multi-panel photographic juxtapositions of movie stills with vinyl and paint interventions—the visual equivalent of a complex sentence, requiring extensive parsing and interpretation. (They also inspired the delightful, crowd-sourced Instagram @BaldessariYourLife , started by artist Steven Wolf, which will repost submitted photos with signature dots added.)

Nam June Paik , another artist central to SAAM’s collection, apparently gave Baldessari one of his favorite compliments when he said, “What I like most about your work is what you leave out.” By creating pockets of mystery in the fabric of the everyday, Baldessari’s art leaves space for the viewer, not only to attend to the process of meaning-making in the gallery, but equally in their everyday engagement with a world of images. Perhaps like a lesson from a houseplant, the inanimate work becomes a teacher, training us how to see and speak anew.

Coda:

While an obituary in the New York Times used to be my measure of lifetime achievement (and Baldessari got not one but two! ), I now think the kind of endless scroll of individual online testimonials that have flowed for this towering figure with a huge heart is a bigger sign of a life well-lived. Even more touching is how many come from former students, mentees, studio assistants attesting to his generosity of spirit and wisdom…and how many of those on Instagram come from younger feminist, queer and/or artists of color, who he supported at critical moments in their education and careers.

May he rest in peace while his work continues to blaze a trail for future generations. Did I mention he lit a decades’ worth of painting on fire and baked them into cookies that were acquired by the Hirshhorn? To learn more, read Stale Cookies in a Jar .

I think my greatest regret now is only having known Baldessari through his art.