Article continues below

Turkish breakfast – a meal of epic proportions based around an often daunting array of cheeses, olives, egg dishes, jams, grilled sausage and cup after cup of black tea – is among the country's finest culinary rituals.

And while the most important meal of the day is cherished and taken seriously throughout the country, its heartland is the eastern city of Van.

Turkish breakfast is among the country's finest culinary rituals

Van and breakfast are synonymous in Turkey, and Van-style breakfast restaurants have opened to fanfare in Istanbul and Ankara, serving regional delicacies such as the famous otlu peynir, a slightly crumbly, potent cheese spiked with an herb called sirmo , locally referred to as 'wild garlic’. And while some of these establishments may be representing the city well, to truly experience the famous breakfast, you need to go to the source.

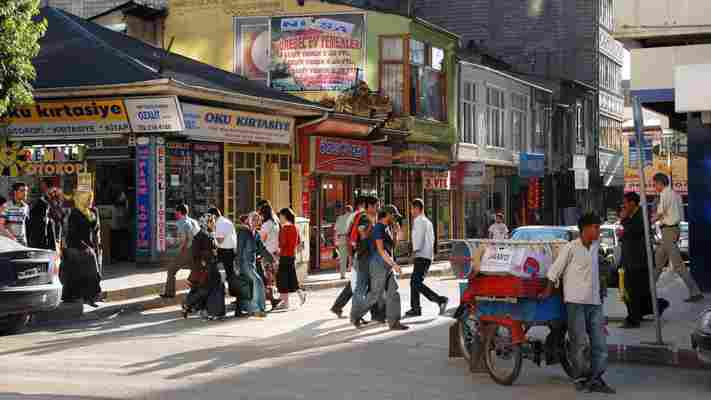

Van, a city of half a million with a majority Kurdish population, is an hour's drive from Iran and feels like a border town. In late spring, the weather is hot but dry, and cools down in the evening. Verdant mountains dominate the horizon, while the lowlands are dotted with wildflowers. Nearby is Lake Van, the largest in the country and home to the idyllic Aghtamar Island, where grey rabbits can be found scampering around a 10th-Century Armenian cathedral.

The city of Van in eastern Turkey is synonymous with breakfast (Credit: rob brimson/Alamy)

You may also be interested in: • A nation changed by breakfast • The breakfast that ended a war • How Switzerland transformed breakfast

This past June, I went to the city to get my hands on its celebrated breakfast, which is so integral to the city that a backstreet parallel to the main boulevard is unofficially known as ‘Breakfast Makers Street’, home to some of the city's most iconic purveyors of the most important meal of the day. In 2014, more than 50,000 people assembled in Van to break the Guinness World Record for the largest-attended breakfast .

Though my visit coincided with the holy month of Ramadan, where observant Muslims fast from the break of dawn until evening, I figured that the city's breakfast restaurants still would stay open around the clock. This was a mostly incorrect assumption, though a number of places did open in the evening in preparation for the early morning suhur meal, eaten by those who are about to embark on their day-long fast. Breakfast Makers Street was having its cobblestones replaced, meaning the usual mass of outdoor tables and chairs was gone. The breakfast restaurants were mostly closed, except for one. Sütçü Selim (Milkman Selim) had old newspapers covering the windows, providing a discreet environment for those not fasting to enjoy their meals.

All of the ingredients are natural and belong to us

Selim's brother Kadir Inal quickly put together a nine-plate spread perfect for one person. While a group of four would be well-equipped to order everything on the menu at a Van breakfast joint (some menus include as many as 30 items), I wanted to skip the nonessentials, including jam, marmalade, chips and hazelnut paste, to focus on the Van specialities. Van cacığı is a ramped-up tzatziki, with chopped long, green peppers, parsley and onion added to the garlic and cucumber. This was served beside a delightful, yellow-tinged dollop of creamy butter. The otlu peynir was fresh and vibrantly flavourful in a way that I’d never had it in my hometown of Istanbul. There was murtuğa , a thick, crumbly dish made of eggs, butter and flour; and a fried egg topped with kavurma, braised lamb or beef.

“It's because all of the ingredients are natural and belong to us,” Inal said when I asked why Van's breakfast is so famous. He said that the sirmo that gives the otlu peynir its signature kick is sourced from the nearby mountains, and the butter comes from the nearby district of Özalp.

Turkish breakfasts consist of an array of cheeses, olives, egg dishes, jams and fresh vegetables (Credit: Sanyalux Srisurin/Alamy)

The next day was filled with hopes of having breakfast by at least lunchtime, though I couldn't find another place that was open prior to the iftar fast-breaking dinner. At around 21:00, I hungrily shuffled into Bak Hele Bak , an expansive dining area decked out in handmade carpets and local kitsch. Sixty-one-year-old Yusuf Konak, who considers himself something of an ambassador for Van breakfast, has run the place since 1975. The walls were lined with photos and newspaper clippings, many featuring the grinning, energetic Konak himself.

“At 01:00 for suhur during Laylat al-Qadr, we served breakfast for free for 1,000 people,” he said, referring to the holy Ramadan night that occurred the day before my visit to the restaurant. He added that he also has served breakfast to Armenian guests of the cathedral on Aghtamar Island.

“Culture has no party, no religion. Within culture there are people, and people are equal. For that reason, this is a house of breakfast culture,” he said.

I requested a breakfast similar to the one I had at Sütçü Selim, and again marvelled at the cacığı (which Konak insisted a Van breakfast is incomplete without) and the sharply flavourful otlu peynir , also enjoying a plate of green and black olives (the one thing coming from outside Van) and another kavurma - topped egg encased in a small copper pan. The cold items came out with a basket of fresh flatbread, and the egg dish came out later, cooked to order. I had a thermos of tea on my table.

Otlu peynir, a slightly crumbly cheese spiked with ‘sirmo’ (wild garlic) is a breakfast staple in Van (Credit: Paul Benjamin Osterlund)

Heading back downtown, the city centre had transformed into a massive open-air market after iftar, with dozens of street vendors grilling liver and chicken kebab and ears of corn, and serving tea from impressive mobile samovars. Everyone was out and about, and the cool air sliced through the heavy, tantalising grill smoke. Youngsters hawked fake name-brand clothing on the crowded pavements, and pedestrian-only alleyways lined with coffee shops were jam-packed with patrons.

One hole-in-the-wall breakfast spot that had come highly recommended had their doors open but were not serving food, but I was lucky to find a similarly rustic establishment on my last evening in town. The Van specialties quickly arrived at Yeni İmsak Kahvaltı Salonu and the tea kept coming as fast as I drank it. I enjoyed my last wedge of otlu peynir. A family sauntered in and sat at a table near the expansive counter, perhaps for an early suhur. It was my second late-evening breakfast in two days, and the cheapest of the three at a mere 15 Turkish Lira (£2.50). Outside, the streets were still humming with the quixotic energy the city enjoys in the evenings during Ramadan.

Yusuf Konak: “Within culture there are people, and people are equal. For that reason, this is a house of breakfast culture” (Credit: Paul Benjamin Osterlund)

It wouldn't be long for I partook in another decadent Turkish breakfast with friends in Istanbul, sharing as many plates as could fit on a table for four. Similar arrangements are available in Van, particularly at the touristy places near the shore of Lake Van. But the breakfast in Van boils down to the traditional specialties made with the freshest, top-quality ingredients gleaned from around the province. They do not taste the same in Istanbul, and are worth travelling across the country for, even if you have to wait until after sunset to partake.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.