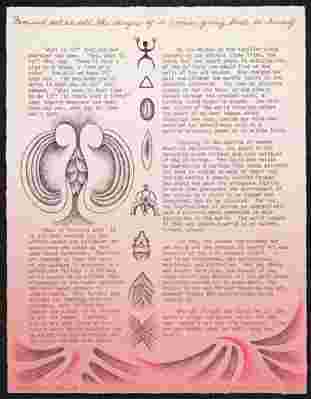

The dollhouse-pink postcard appeared in artists’ inboxes in 2019 with the same prompt that had been sent via snail mail in 1976: “If you consider yourself a feminist, would you respond by using one 8 ½” x 11” page to share your ideas on what feminist art is or could be.”

“I haven’t a clue what feminist art is,” scrawled Martha Lesser, one of the 200-plus creatives who responded to the prompt in the 1970s. Others typed out five-paragraph essays, sketched a self-portrait, or even submitted an image of an umbilical cord magnified under a microscope. Their responses became part of a 1977 exhibition in Los Angeles organized by feminist activists for the Woman’s Building .

Remakes are in vogue of late, and 43 years after the West Coast original of “What is Feminist Art?” the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art staged its own “recreation of that exhibition,” says Liza Kirwin , the Archives’ deputy director, by posing the same query to a cohort of artists in 2019. The two sets of answers to the still-relevant central question reveal how society’s understanding of feminism, and feminist art, has changed in some ways and stayed static in others.

The ’70s earned its reputation as a “consciousness-raising era” in the art world and the United States at large, Kirwin says. Against the backdrop of second-wave feminist activism and the sexual revolution, community spaces like the Woman’s Building provided mentorship in a world where formal art training involved a host of mostly male instructors. While feminist art itself obviously predated the decade, art historian Linda Nochlin’s influential 1971 essay Why Have There Been No Great Woman Artists? and Judy Chicago’s controversial and very vulvic installation The Dinner Party (1974-79) exemplify the surge in art that directly pondered women’s rights and roles.

For the exhibition’s present-day reincarnation, the Archives of American Art wanted to address a flaw in the original show to ensure that a more representative cross section of artists from the U.S. and abroad participated. To this end, the show’s curator, Mary Savig, assembled an outside advisory group of influential artists, curators and academics whose professional work involves highlighting marginalized artists’ work.

The committee’s roster of visual artists was less white than the ’70s cohort, although still largely (but not exclusively) female-identifying. Some of the original respondents also had the chance to contemplate the question for a second time. The exhibition also presented two exciting firsts for the Archives of American Art, Kirwin says. The wall text appears in both English and Spanish, and the Archives had the opportunity to solicit new materials from a younger group of artists. This contemporary cohort of artists sent 75 answers, among them: a bunch of blue sparkling spirals, typed or handwritten notes, lipstick-smeared paper, a painting of another artist in the studio, decidedly modern screenshots of iPhone messages and more.

Kirwin explains that the show puts the two sets of meditations on feminist art—from 1976-77 and 2019—“in conversation with another.” While the walls are stamped with a few choice quotes from the artwork and papers on display, there’s no one definition of “feminism” provided. Instead the point is for the viewer to take in the artists’ perspectives and draw their own conclusions about what “feminist art” means. “We wanted to really minimize the curatorial point of view in this exhibition,” Kirwin remarks.

Nevertheless, here’s some useful context: Feminism and the “women’s movement” have increased in popularity since the first showing of “What is Feminist Art?” In a 1986 Gallup poll , only around 10 percent of women identified as “strong” feminists, and nearly a third said they wouldn’t consider themselves feminists. Fast-forward to 2016, and six out of every ten women pronounced themselves either a “strong feminist” or “feminist” in a Washington Post -Kaiser Family Foundation poll .

Despite what the numbers suggest is a growing mainstreaming of feminism, Kirwin says she noticed “a frustration” in some of the reflections the original artists provided in 2019, the second time they’d been asked (formally, at least) to define feminist art. Harmony Hammond , a leading figure in the movement, proclaimed that feminist art was “STILL DANGEROUS” in bold lettering on her current 8.5-by-11-inch sheet. In the original show, she’d called it “Dangerous,” too, but nestled that adjective in a longer letter and not written it in such large, capital letters.

Other 2019 responses emphasized the importance of intersectionality—understanding the interconnection of various forms of discrimination—in today’s feminist art. “In 2019, our understanding has expanded. . . Feminist art is willing to fight against and refuse to perpetuate white supremacy and racism,” wrote poet Terry Wolverton , her words arranged in a pink spiral. Potter Nora Naranjo Morse explained that the line of Tewa Pueblo women she comes from exemplified feminism without being conscious of the Western definition of the term. In typed white letters on a background of inky black paper, textile and visual artist LJ Roberts objected to the project’s lack of honoraria, arguing that unpaid art takes time away from other important artistic pursuits: “As a queer, non gender-conforming, non-binary person…being asked to produce work for free undermines critical goals that feminist art aims to achieve.”

Other themes stood out in the original and contemporary 8.5-by-11 statements. Howardera Pindell’s 2019 statement that “Feminist artists are free from feeling that they have to imitate Euro/American male culture in form, style, media ect.,” echoes Grace Graupe-Pillard’s 1976 wish for “No rules—no pigeonholing” of art created by feminists. And Joyce Kozloff’s 21st-century answer reiterated the definition the critic Linda Nochlin offered back in 1970: “Feminism is justice.”

The exhibition, with its wide array of responses, aims to be thought-provoking. Asked what she hopes visitors leave the gallery thinking about, Kirwin replies simply, “I hope they ponder the question.”

Currently, to support the effort to contain the spread of COVID-19, all Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.C. and in New York City, as well as the National Zoo, are temporarily closed. “What is Feminist Art: Then and Now” is scheduled to be on view through November 29, 2020 in the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery on the first floor of the Old Patent Office Building at 8th and F Streets in Washington, D.C., also home to the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery . Check listings for updates. The exhibition is a project of the Smithsonian's American Women's History Initiative.

The Lost Kusamas

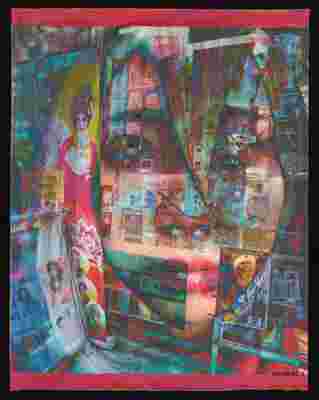

2019 saw many wonderful and important works enter SAAM’s collection–photographs by Dawoud Bey , My Dreams, My Works Must Wait Till After Hell by the duo Girl, (Chitra Ganesh and Simone Leigh), a mixed-media work by AfriCOBRA co-founder Jeff Donaldson , and Judith Baca’s historic mural Uprising of the Mujeres , among many others. But the most surprising new acquisition comes from our Joseph Cornell Study Center—a trove of Cornell’s studio effects saved after the artist’s death and administered by SAAM’s Research and Scholars Center. Amidst the correspondence, photographs, and ephemera of Cornell’s life, archivist Anna Rimel discovered four small watercolors by Yayoi Kusama . These unexpected treasures have now been transferred into SAAM's collection.

Today, Kusama is considered one of the most important artists in the contemporary art world, among the first artists from Asia to gain global prominence after World War II. It was a different story when Cornell and Kusama first met: he was an established figure in New York, known for his intricate box constructions; she was young and struggling. The two became friends in 1962 and remained close until Cornell’s death a decade later. Cornell dedicated poems and artworks to Kusama, and they spent time at his home in Queens, where he lived with his mother, sometimes sketching each other. Aware of her financial difficulties, Cornell occasionally gave the younger artist pieces of his to sell, allowing her to earn a commission. He also bought the four works that are now in SAAM’s collection—a purchase recorded by a receipt dated August 22, 1964, also preserved in the Cornell Study Center.

Rendered in watercolor, ink, pastel, and tempera paint, these delicate compositions were created in the mid-fifties and represent a crucial body of work that bridged Kusama’s transition from Japan to the United States. Their imagery suggests microscopic or cosmological topographies, intimate spaces that she would later expand in her Infinity Mirror Rooms. They were among the roughly 2,000 works on paper Kusama brought with her when she left Japan in 1957, hoping to sell them to support herself. Arriving in New York City after a brief sojourn in Seattle, Kusama quickly become part of the avant-garde scene, creating astonishingly innovative new art in the context of pop and Happenings, minimal and post-minimal art, and by the late 1960s, the hippie counterculture.

In 1973 Kusama returned to Japan. Among the things she brought home with her were magazine cuttings that Cornell had given to her, from which she made intricate collages—surrealist-inflected images that were, in part, an elegy to her friend. The works testify to her deep bond with Cornell—a relationship Kusama has described as passionately romantic yet platonic—as well as to the artist’s remarkable transnational career and unique role within the story of post-war American art.

Artists Who Paint With Their Feet Have Unique Brain Patterns

Tom Yendell creates stunningly colorful landscapes of purple, yellow and white flowers that jump out of the canvas. But unlike most artists, Yendell was born without arms, so he paints with his feet. For Yendell, painting with toes is the norm, but for neuroscientists, the artistic hobby presents an opportunity to understand how the brain can adapt to different physical experiences.

“It was through meeting and observing [Yendell] doing his amazing painting that we were really inspired to think about what that would do to the brain,” says Harriet Dempsey-Jones, a postdoctoral researcher at the University College London (UCL) Plasticity Lab . The lab, run by UCL neurologist Tamar Makin, is devoted to studying the sensory maps of the brain.

Sensory maps assign brain space to process motion and register sensations from different parts of the body. These maps can be thought of as a projection of the body onto the brain. For example, the area dedicated to the arms is next to the area dedicated to the shoulders and so on throughout the body.

Specifically, Makin’s team at the Plasticity Lab studies the sensory maps that represent the hands and the feet. In handed people, the brain region dedicated to the hands has discrete areas for each of the fingers, but unlike these defined finger areas, individual toes lack corresponding distinctive areas in the brain, and the sensory map for feet looks a bit like a blob. Dempsey-Jones and colleagues wondered whether the sensory maps of ‘foot artists’ like Yendell would differ from those of handed people .

Dempsey-Jones invited Yendell and another foot artist named Peter Longstaff, both part of the Mouth and Foot Painting Artists (MFPA) partnership, into the lab. The scientists interviewed the two artists to assess their ability to use tools designed for hands with their feet. To Dempsey-Jones’ surprise, Yendell and Longstaff reported using most of the tools they were asked about, including nail polish and syringes. “We were just continuously being surprised at the level of ability they had,” Dempsey-Jones says.

Then the researchers used an imaging technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, to develop a picture of the sensory maps in Yendell and Longstaff’s brains. The researchers stimulated the artists’ toes by touching them one at a time to see which specific parts of the brain responded to the stimuli. As they stimulated each toe, distinct areas lit up. They found highly defined areas in the brain dedicated to each of the five toes, one next to the other. In the control group of handed people, these toe maps did not exist.

For Yendell, who had been part of brain imaging studies before, the defined toe maps didn’t come as a surprise. “I'm sure if you take a table tennis player who has a very different way of using their hand, the brain map will be slightly different to the average person. I think there's lots of instances where it wouldn't be out of the ordinary to be different in any way.”

Scientists have known for a long time that the brain is malleable. With training and experience, the fine details of sensory maps can change. Maps can be fine-tuned and even reshaped. However, scientists had never observed new maps appearing in the brain. Dan Feldman, a professor of neurobiology at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not part of the study, believes the findings are a striking demonstration of the brain’s capacity to adapt. “It builds on a long history of what we know about experience-dependent changes in sensory maps in the cortex,” he says. “[The research] shows that these changes are very powerful in people and can optimize the representation of the sensory world in the cortex quite powerfully to match the experience of the individual person.”

The research has important implications for the newly emerging technology of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). BCIs are devices that can translate brain activity into electrical commands that control computers. The technology is intended to improve the lives of people without limbs and people recovering from a stroke. Understanding the fine details of how the body is represented in the brain is critical for more accurate development of brain-computer technologies.

“If you want to have a robotic limb that moves individual digits, it's very useful to be able to know that you have individual digits represented, specifically in the brain,” Dempsey-Jones says. “I think the fact that we can see such robust plasticity in the human brain argues that we can maybe gain access to these changeable representations in a way that might be useful for restoring sensation or for a brain-machine interface,” Feldman adds.

But a fundamental question remains: How do these toe maps arise? Are they present at birth and maintained only if you use your toes frequently? Or are they new maps that arise in response to extreme sensory experiences? Dempsey-Jones believes, as with most processes in biology, the answer is a little bit of both. She says there is probably a genetic predisposition for an organized map, but that you also need sensory input at a particular time of life to support and fine-tune it.

Yendell recalls scribbling and even winning a handwriting competition when he was two or three years old. The Plasticity Lab wants to understand how these early events drive the establishment of toe maps. By looking at early childhood experiences, Dempsey-Jones and her team might be able to identify which timepoints are necessary for the development of new sensory maps in the brain. “We've found that if limb loss occurs early enough, you have brain organization similar to someone born without a limb,” she says.

Once scientists determine the periods of development that generate this unique organization of toe maps, the improved understanding of the brain could lead to better technologies for people who are disabled or missing limbs. Yendell, who is on the board of the MFPA, is more than happy to contribute to these types of studies. “Anything that helps other people understand and overcome things, then you've got to do it.”

This piece was produced in partnership with the NPR Scicommers network.