Mingering Mike may be one of the most prolific soul singers in American history, but he never played a live show and you won’t find his recordings online. That’s because Mike, and his musical career, were invented in the 1960s by a Washington, D.C.-based artist known only by the alliterative alias, “Mingering Mike.”

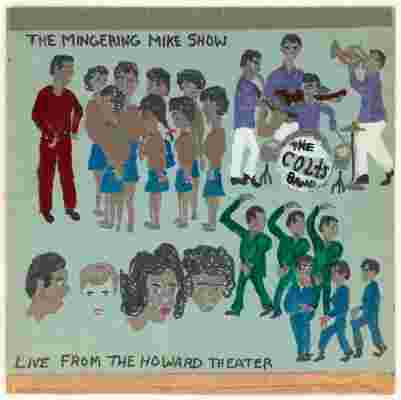

As a young man, Mike fabricated a vivid and fantastical world of live performances, studio albums and soundtracks for which he created his own hand-painted facsimiles of LP album covers. Some of his works were even designed with shrink wrap and liner notes, further blending reality and fiction.

Mike’s imagined discography explores pressing cultural issues like the Vietnam War, poverty, and drug abuse, as well as more traditional subjects like love and relationships. More than anything, his work is a celebration of the music he loved. Between 1968 and 1977, Mingering Mike wrote more than 4,000 songs, created dozens of real recordings using acetate, reel to reel and cassette players, and drew hundreds of labels and album covers. Four years ago, his early fantasy-life creations were on display in the popular exhibition "Mingering Mike's Supersonic Greatest Hits" at the Smithsonian American Art Museum .

A new episode of the museum’s web series “Re:Frame” explores one of Mike’s pieces, The Mingering Mike Show Live From the Howard Theatre , and its connection to the historic Washington, D.C. venue.

The Re:Frame team recently sat down with the artist Mingering Mike to chat about the world he constructed and what it feels like to look back on his work 50 years after it was created. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you start making artwork?

Mike: I started making artwork back in 1968. My first album cover was Sit'tin By The Window .

And what inspired you to start?

What inspired me to start was the various TV shows and movies back in that era. I was just saying to myself: "Hey, I could do that." Or if I went to a movie, and the music wasn't all that good, I'd say: "Hey, I could do a better theme song than that." And so that's how it started with the music. At first all I could think of were titles, and so I would write down that title and then eventually something would come in my head.

Who were some of your favorite musicians at that time?

My favorite musicians at the time were Jimmy Walker, Otis Redding, Bobby Darin, Julius Larosa, Stevie Wonder, a lot of them. My all-time favorite song would be “Satisfaction” by The Rolling Stones. Then after that, it would be James Brown with “Papa's Got a Brand New Bag.” And it goes on and on.

Did you ever take any art classes?

Well it was a requirement back then, like third, fourth, fifth, sixth grade. I recall drawing a dollar bill on a construction paper—I think I might have been nine—and it looked pretty good. It looked so good, I thought about taking it to the store!

Is that how you got interested in art?

Not really. While I was there in the school, I wasn't thinking of anything but just getting out there at recess time, until the bell ring for you to come back. But you know, some things just linger with you. It just stuck in the back of my head, until the music part started coming out. Then when I started writing songs, I wanted to have something to go with the songs, so I started creating albums.

How many works do you think you've created, in total?

I've probably made over 60 albums.

What materials did you use?

The material that I'd use were acquired from, it's CVS now, but it used to be called People's Drug. I used to go in there and get the poster board, and then I would go down to the local store, that sells paint and purchase various paints, and I would get markers, and then I would start on the project, whatever I was thinking about. Sometimes someone could be saying something, and I'd think: "Oh, that's a good lyric to a song, that I could start something with that." Then I can imagine different things and I would just put it on the paper and work it onto the cardboard.

Most of [the records] would take maybe like, a month. Or, if I was really interested in it, it might take maybe like, two and a half weeks, or so. The thing is, you've got to be perfect with those album covers there, because you make a mistake, then you have to start all over. And if you start all over, you might not have the dynamics of how you had it.

Do you have any special connection to the Howard Theatre ?

The connection I have with the Howard Theatre is when I was going there, seeing all the various groups. Jimmy Walker, James Brown, Motown Revue—and it was fantastic to me.

My two older brothers, they used to work there, so I used to be able to get in sometimes for free. Matter of fact, my oldest brother used to be the one that ran the district theaters, at the time. So I can go to any theater, if he was working there, and watch a movie. So that was great for a kid growing up and didn't have too much money.

Did you ever expect anyone to see this work that's now part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum's collection ?

I never expected anyone to be witness to some of the stuff that I've done, and I find it so fantastic that people come to see. And they will leave comments, and most of them are great comments.

How does it feel to look back at your work, 50 years after you made it?

It makes me feel like I'm an old fella. I said: "Good gosh, 50 years! My gracious!" And it's amazing that it still holds up.

Mingering Mike's works are held in the collections of the Smithsonian Art Museum. The artwork The Mingering Mike Show Live From the Howard Theatre is currently not on view.

Rare Chance in 2020 to See This Classic Danish Masterwork

For centuries, artists have gathered together to share ideas, trade techniques, show support and to occasionally pose for one another. They have also been competitive rivals, sniping at one another in good-natured and not so good-natured ways.

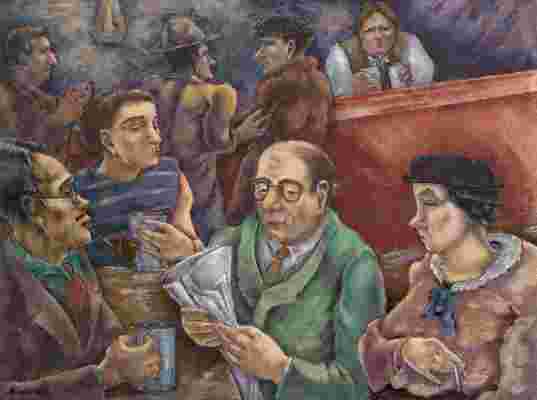

So when a quartet of artists from a far-flung Denmark fishing village turned artist colony came together to see the unveiling of one painter’s portrait of another, there was enough skepticism, consideration and rumination to warrant a whole other work—Michael Ancher’s monumental 7-by-5 foot 1906 oil on canvas, Kunstdommere (Art Judges) .

Ancher’s group portrait captured a handful of Danish cultural luminaries of Scandanavia’s Modern Breakthrough movement of the 1870s and 1880s, and that only helped to make it a beloved national masterwork.

Now, the artwork is the centerpiece of the third Portraits of the World exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington. The series borrows a key work from a chosen country, and surrounds it with augmenting pieces from the museum’s own collection. Earlier shows have showcased works from Switzerland and Korea .

In this case, the competitive camaraderie of the Skagen village artist colony is put in context with works that largely show artists working together in quite a different setting—the teeming studios of early 20th century New York City.

In Kunstdommere , Ancher , one of Demark’s best known artists, depicted the reactions of four notable figures—dramatist Holger Drachmann , artist Peder Severin Krøyer , artist Laurits Tuxen , along with Jens Ferdinand Willumsen , a younger artist.

Willumsen’s work would eventually encompass abstraction, but at the time, the Modern Breakthrough artists of Denmark were already making their mark with evocative, realistic depictions of everyday life and not just the usual romanticized views of royalty. That aim sparked their move to a remote fishing village to do their work.

“One of the things that’s so great about this painting is that it’s a mini history lesson on Danish culture,” says the Portrait Gallery’s curator of prints and drawings Robyn Asleson , who put together the show. “These are the greatest artists and literary figures in the country—all in this one, monumental painting.”

They are still well-regarded figures in their country. A profile of Ancher and his wife—from a portrait by Krøyer—was on the 1000 Danish Kroner banknote from 1998 to 2012.

Of the four in the painting, Tuxen, in his white suit and red beard, was the “royal portraitist of favor; he painted the royal court, he painted Queen Victoria,” Asleson says. “So he’s a little bit of the old school.”

Krøyer, by contrast was the epitome of the Modern Breakthrough. “Perhaps the most famous and loved artists in Denmark, with his scenes of fisherman and their lives of danger and hardship near the water. He is explaining to this group, this portrait we can’t see,” Asleson says.

Underlying the relationship among artists was competition, and some specific grousing about how long it took to sit for such a portrait. “That’s the tension that’s under the surface among these friends,” she says. “It’s like: ‘What’s taking you so long?’”

Asleson says she had hoped to augment the painting with examples from rural American arts colonies of that era, but found there were no portraits in their collection from communities in Ogunquit, Maine or Provincetown, Massachusetts .

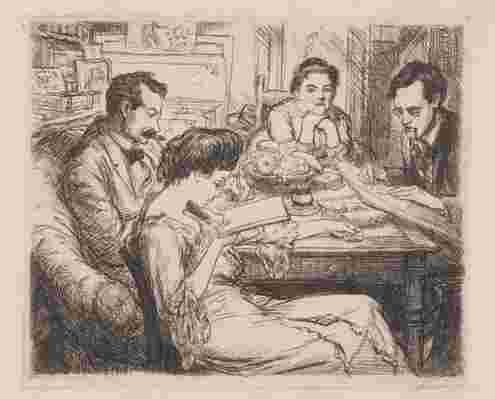

“Luckily we have all these great portraits of artists’ communities in New York,” she says. It includes the early Ashcan School of Robert Henri represented in a 1906 etching by John Sloan, who also appears in a Marion D. Freeman etching of a workshop at the Art Students League.

The painter George Bacon depicts his circle at a speakeasy in a 1933 painting that had been hanging at a government building until now. Peggy Bacon shows the Whitney Studio Club drawing class in a frenzy while things are calmer in Mabel Dwight’s 1928 lithograph of the Weyhe Gallery.

Alfred Stieglitz’s modern art circle is represented in a pair of works by Marius de Zayas and Francis Picabia sharply critical of Stieglitz’s perceived lack of forward movement.

American art’s own Modern Breakthrough arose from Abstract Impressionism, so there are a couple of striking Hans Namuth photographs from the early 1950s—one of Jackson Pollock , Barnett Newman and Tony Smith at Betty Parsons’ gallery and another of Elaine and Willem de Kooning with one of his works (as if to show that she’s not the model for his jagged abstractions of women).

De Kooning is celebrated further in a Red Grooms work that literally breaks through the picture plane with the bicycling artist giving his abstracted woman a ride on his handlebars.

The idea of art judges reflects some other events currently at the museum, where the juried triennial Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition is on display. A Bill Witt shot of Hans Hoffman in his Provincetown studio in the Portraits of the World show hangs quite near a shot from the same session in a photography show called “In Mid-Sentence.”

Portraits of the World: Denmark will hang through October. The Portrait Gallery established a connection with the lending Danish Museum of National History in Hillerød by offering in a return last winter a show of jazz portraits by Herman Leonard.

“We really hope that the art judges in the United States—the visitors to the gallery and the critics—will receive it positively,” Mette Skougaard, director of the lending museum said before the work was shipped.

Currently, to support the effort to contain the spread of COVID-19, all Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.C. and in New York City, as well as the National Zoo, are temporarily closed. Check listings for updates. “Portraits of the World: Denmark” is scheduled to remain on view through October 12, 2020 at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C.

Mr. Peanut Was the Creation of an Italian-American Schoolboy

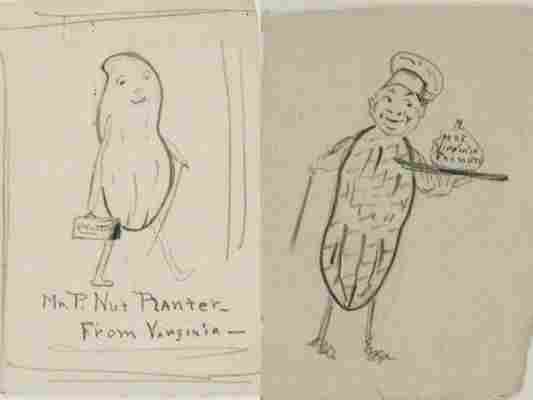

In 1916, Planters Nut and Chocolate Company ran a contest for a trademark. Antonio Gentile, a resident of Suffolk, Virginia, the peanut-growing capital of the state, began sketching possible entries for the contest. He drew a friendly, humanized peanut tumbling, serving nuts, and walking with a dignified cane.

One of his sketches won the contest; Gentile earned $5, and became forever known as the young boy who created Mr. Peanut. Mr. Peanut himself got a little polish from a graphic artist and went on to a long career as the classy, and until recently, silent spokes-character for their product.

In 2014, Robert Slade, the nephew of Antonio Gentile, contacted the National Museum of American History to ask if the Smithsonian would be interested in the original drawings for the national collections. Serendipitously, we had just—the same day—collected a large, cast-iron Mr. Peanut (pictured above), and here were the drawings that inspired that dapper figure. What luck! As the curators learned more about the history of the trademark from Mr. Slade, a more interesting story unfolded about the life of that imaginative young boy and his relationship to the Planters founder. We're delighted that Mr. Slade can share that story here:

"Antonio Gentile, our uncle, was born in 1903 in Philadelphia to Italian immigrant parents. He and his family later moved to Suffolk, Virginia, so our grandfather could utilize his tailoring skills.

"Tony, as he was known, assimilated into the small-town southern culture and the local Italian community easily. Both influences shaped him. Suffolk allowed him to flourish and grow independent while the Italian connection allowed access to others of similar heritage, such as Amedeo Obici, one of the founders of Planters Nut and Chocolate Company. Our two families were close despite a wide financial disparity between them, with Amedeo and Louise Obici taking a personal interest in all of the children and even hosting our family on their family farm on numerous occasions.

"Tony became an Eagle Scout and graduated as valedictorian of his high school class in 1920. He went on to the University of Virginia, earning honors and three degrees: undergraduate, medical, and a masters in science.

"After four years of specialized obstetrical surgical study, his medical career took him to Elizabeth Buxton Hospital in Newport News, Virginia, where he was one of the youngest surgeons admitted as a Fellow in the American College of Surgeons. He became a fixture in the social and fraternal world of the "Peninsula," as that part of Virginia is known.

"In December 1938, he married Delcy Ann Maney, but their marriage lasted less than a year; for Tony passed away of a heart attack in the early hours of November 16, 1939, while on duty at the hospital. His passing was noted prominently on the front page of several local newspapers, and in an editorial tribute on November 23, 1939, the Times-Herald of Newport News noted:

"Yet to many, our uncle will forever be known solely as the schoolboy who, in a school contest in 1916, received $5 for drawing the figure that became Mr. Peanut, the trademark for Planters Nut and Chocolate Company. However, it was those crude pencil drawings, later enhanced by a commercial artist, together with the familial relationship with the company's founder, Amedeo Obici, which enabled him to fulfill his life's ambition of service to others. Had it not been for Mr. Obici's personal interest and generosity, Tony's education may not have been as extensive and his achievements as meaningful. It truly was the simple peanut figure that became an advertising icon which defined his life and his impact as a person."

To learn more about Mr. Peanut as a spokes-character, check out this episode of our Founding Fragments video series: